According to new research from a Duke-led brain imaging study, adults with PTSD have smaller cerebellums.

The cerebellum, a region of the brain known for dealing with movement and balance, can influence mood and memory, both of which are affected by posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). What is unknown is whether a smaller cerebellum predisposes a person to PTSD or whether PTSD causes the brain region to shrink.

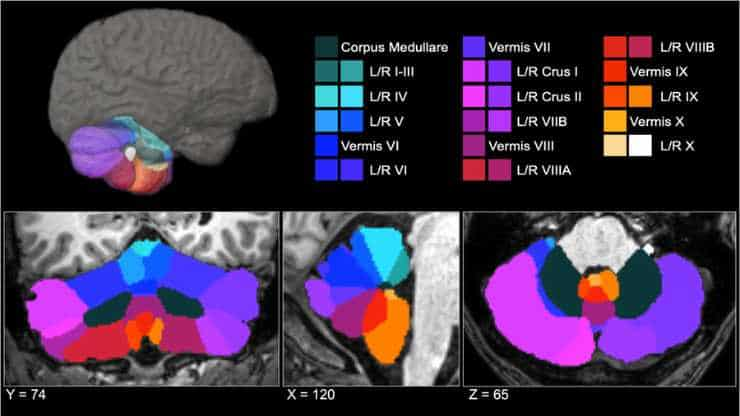

“The differences were largely within the posterior lobe, where a lot of the more cognitive functions attributed to the cerebellum seem to localize, as well as the vermis, which is linked to a lot of emotional processing functions,”

said lead author Ashley Huggins, Ph.D., who helped carry out the work as a postdoctoral researcher at Duke in the lab of psychiatrist Raj Morey, M.D.

Which Came First?

Huggins, who is now an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Arizona, hopes that these findings will persuade others to consider the cerebellum as an important medical target for those suffering from PTSD.

“If we know what areas are implicated, then we can start to focus interventions like brain stimulation on the cerebellum and potentially improve treatment outcomes,”

Huggins said.

The findings have motivated Huggins and her lab to start looking for what comes first: a smaller cerebellum that might make people more susceptible to PTSD, or trauma-induced PTSD that leads to cerebellum shrinkage.

PTSD Brain Regions

PTSD is a mental health disorder caused by watching or experiencing a traumatic incident, such as a vehicle accident, sexual abuse, or military warfare. Though most people who go through a terrible experience are immune to the illness, approximately 6% of adults get the disorder, which is characterized by increased fear and repeating the horrific incident.

Researchers have discovered several brain regions involved in PTSD, including the almond-shaped amygdala, which regulates fear, and the hippocampus, which is a critical hub for processing memories and routing them throughout the brain.

The cerebellum (Latin for “little brain”), by contrast, has received less attention for its role in PTSD.

The cerebellum, a grapefruit-sized lump of cells that appears to have been slapped beneath the back of the brain as an afterthought, is most known for its function in managing balance and choreographing complicated movements such as walking or dancing. However, there is a lot more to it than that.

Complex and Dense

The cerebellum region is very complex.

“If you look at how densely populated with neurons it is relative to the rest of the brain, it’s not that surprising that it does a lot more than balance and movement,”

Huggins said.

Dense is probably an understatement. The cerebellum accounts for only 10% of total brain volume but contains more than half of the brain’s 86 billion nerve cells.

Researchers recently discovered variations in the size of the tightly packed cerebellum in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Most of that research, however, is constrained by a tiny dataset (fewer than 100 participants), broad anatomical boundaries, or a singular emphasis on specific patient populations, such as veterans or sexual assault victims suffering from PTSD.

2% Smaller Cerebellums

Dr. Morey of Duke University, along with over 40 other research groups participating in a wider data-sharing program, combined their brain imaging scans to study PTSD as extensively and generically as possible. The group received images from 4,215 adult MRI scans, almost one-third of whom had been diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder.

“I spent a lot of time looking at cerebellums,”

Huggins said.

She manually spot-checked every image to ensure the boundaries drawn around the cerebellum and its various subregions were precise, despite using automated technologies to analyze the thousands of brain scans. The end outcome of this meticulous research was a rather straightforward and consistent finding: PTSD patients had cerebellums that were around 2% smaller.

Huggins discovered similar cerebellar decreases in persons with PTSD when she focused on specific parts of the cerebellum that regulate emotion and memory. She also discovered that the smaller a person’s cerebellum was, the worse their PTSD was.

“Focusing purely on a yes-or-no categorical diagnosis doesn’t always give us the clearest picture. When we looked at PTSD severity, people who had more severe forms of the disorder had an even smaller cerebellar volume,”

Huggins said.

Next Steps

The findings are an essential first step in determining how and where PTSD affects the brain.

Huggins noted that there are over 600,000 different combinations of symptoms that might lead to a PTSD diagnosis. It will also be vital to consider whether different PTSD symptom combinations have distinct effects on the brain.

At present, however, Huggins’s aspiration is that this research aids in the recognition of the cerebellum as a potential target for novel and existing treatments for individuals with PTSD, as well as a significant regulator of complex behavior and processes extending beyond gait and balance.

“While there are good treatments that work for people with PTSD, we know they don’t work for everyone. If we can better understand what’s going on in the brain, then we can try to incorporate that information to come up with more effective treatments that are longer lasting and work for more people,”

Huggins said.

Abstract

Although the cerebellum contributes to higher-order cognitive and emotional functions relevant to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), prior research on cerebellar volume in PTSD is scant, particularly when considering subregions that differentially map on to motor, cognitive, and affective functions. In a sample of 4215 adults (PTSD n = 1642; Control n = 2573) across 40 sites from the ENIGMA-PGC PTSD working group, we employed a new state-of-the-art deep-learning based approach for automatic cerebellar parcellation to obtain volumetric estimates for the total cerebellum and 28 subregions. Linear mixed effects models controlling for age, gender, intracranial volume, and site were used to compare cerebellum volumes in PTSD compared to healthy controls (88% trauma-exposed). PTSD was associated with significant grey and white matter reductions of the cerebellum. Compared to controls, people with PTSD demonstrated smaller total cerebellum volume, as well as reduced volume in subregions primarily within the posterior lobe (lobule VIIB, crus II), vermis (VI, VIII), flocculonodular lobe (lobule X), and corpus medullare (all p-FDR < 0.05). Effects of PTSD on volume were consistent, and generally more robust, when examining symptom severity rather than diagnostic status. These findings implicate regionally specific cerebellar volumetric differences in the pathophysiology of PTSD. The cerebellum appears to play an important role in higher-order cognitive and emotional processes, far beyond its historical association with vestibulomotor function. Further examination of the cerebellum in trauma-related psychopathology will help to clarify how cerebellar structure and function may disrupt cognitive and affective processes at the center of translational models for PTSD.

Reference:

- Huggins, A.A., Baird, C.L., Briggs, M. et al. Smaller total and subregional cerebellar volumes in posttraumatic stress disorder: a mega-analysis by the ENIGMA-PGC PTSD workgroup. Mol Psychiatry (2024). Doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-02352-0

Image: Cerebellum parcellation for a representative subject. A three-dimensional display is presented in the upper half of the figure, along with coronal (left), sagittal (middle), and axial (right) views below. Credit: Mol Psychiatry (2024). Doi: 10.1038/s41380-023-02352-0