During adolescence, social and emotional development play a new role in an individual’s overall well-being. As adolescents navigate through this vital period of life, they acquire a greater ability to understand, experience, express, and manage emotions, as well as foster meaningful relationships with others.

Adolescent development does not always proceed along the same course for every person, but emotion regulation, identity development, and relationships with others are usually a focus.

Adolescence is often characterized by heightened emotions and emotional instability. Developing healthy emotional regulation strategies is an essential component of social emotional development during this time.

Adolescents learn to identify, process, and express their emotions in appropriate ways, which in turn enhances their ability to face challenges and adapt to new situations.

Identity and Relationships

One of the most significant changes in adolescence pertains to identity development. As adolescents explore various domains, such as academic, social, and personal interests, they progressively form a sense of self.

During this stage, teenagers typically undergo self-discovery, refining their beliefs, values, aspirations, sense of autonomy, and preferences. The process of identity development often involves reassessing pre-established norms and engaging in self-reflection. Establishing a stable identity during adolescence is integral to long-term emotional well-being and equips an individual with a congruent self-concept that carries into adulthood.

Adolescents’ social emotional development is considerably influenced by their relatedness with others. As they grow older, the importance of peer relationships and friendships increases, while the dependence on familial relationships diminishes.

The cultivation of healthy, supportive friendships during adolescence provides emotional security and an opportunity for identity exploration. In addition, adolescents begin to form romantic relationships, which offer them the chance to explore new emotional experiences and deepen their understanding of intimacy.

Interactions with teachers, mentors, and other adult figures allow adolescents to develop social support networks beyond their immediate family members.

Social Development in Adolescents

During adolescence, children increasingly establish peer groups that are somewhat insular in nature (e.g., “cliques” or “crowds”), frequently with a common interest or values (e.g., “stoners,” “nerds”, “jocks”). For instance, they may develop similar interests, fashion preferences, or attitudes towards authority. In a positive context, these interactions can foster a sense of belonging, enhance self-esteem, and teach valuable social skills.

Peer groups have been proposed as an interim support source for adolescents as they gain independence from their families. Research demonstrates that the relevance of peer group participation to youth increases in early adolescence before declining in later adolescence.

It’s also during adolescence that peer social relationships may become more complex, with the emergence of romantic interests and intimate bonds. Girls are more vulnerable to disruption in these relationships than boys because they have more relationship-oriented goals related to intimacy and social approval. Successfully navigating these newfound experiences often paves the way for healthy relationship patterns in adulthood.

Family Dynamics and Support

Family relationships also significantly contribute to an adolescent’s social development. A home environment that nurtures effective communication, trust, and mutual respect can build strong foundations for positive growth. Adolescents with stable family relationships are better equipped to handle challenges, manage emotions, and seek support when needed.

On the contrary, conflict or lack of support within the family unit can adversely affect an adolescent’s well-being, potentially leading to emotional and social difficulties in the future.

School Environment and Socialization

The school setting serves as a major context for adolescents’ social-emotional development. In an inclusive and supportive environment, academic institutions have the ability to foster essential life skills such as goal-setting, problem-solving, and cooperation.

Furthermore, schools offer numerous opportunities for peer interaction through extracurricular activities, team projects, and sports, which encourages adolescents to develop social bonds and practice their interpersonal skills. Educators’ guidance and expectations can also impact students’ social-emotional growth significantly.

Media and Digital Impact

Today’s adolescents spend an increasingly large amount of time in a digitalized world, where media and online platforms have a noteworthy impact on their emotional development. Media outlets expose young people to various societal norms, cultural values, and communication styles. Adolescents often turn to these platforms for information, validation, and socialization, which can shape their perceptions and expectations about the world.

While some aspects of digital media can enhance connectivity and provide a sense of belonging, excessive reliance on virtual interactions may impede adolescents’ face-to-face communication skills and contribute to feelings of isolation or anxiety.

According to a 2019 study, adolescents who use social media for more than three hours per day are more likely to report high levels of internalizing behaviours than adolescents who do not use social media at all.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health looked at how much time adolescents spent on social media as well as two behaviours that could be indicators of mental health issues: internalizing and externalizing. Internalizing might manifest as social retreat, trouble coping with anxiety or despair, or internalizing feelings. Aggression, acting out, misbehaving, and other visible behaviours are examples of externalizing.

The study showed that any amount of time spent on social media was connected with a higher likelihood of reporting internalizing problems alone as well as concurrent symptoms of both internalizing and externalizing problems.

The study showed no substantial link between social media use and externalizing difficulties on their own. Teens who spent at least three hours per day on social media had the highest likelihood of reporting internalizing problems on their own.

“Social media has the ability to connect adolescents who may be excluded in their daily life. We need to find a better way to balance the benefits of social media with possible negative health outcomes. Setting reasonable boundaries, improving the design of social media platforms and focusing interventions on media literacy are all ways in which we can potentially find this equilibrium,”

said lead author Kira Riehm, MSc.

Adolescence and Emotional Development

During adolescence, individuals undergo significant emotional and cognitive changes, which contribute to the development of their identity and self-perception. Adolescents may start exploring different roles, beliefs, and values as they try to forge a coherent sense of self.

This process is crucial in establishing a stable adult identity and gaining self-awareness. The context of school plays a significant role in providing social opportunities that can either nurture or hinder this formation.

Factors such as family life, peer relationships, and media also impact the way adolescents perceive themselves and their environment. It is essential to provide support and guidance to adolescents during this period to help them build a healthy and resilient identity.

Managing Emotions and Stress

Adolescence is a time when individuals face a myriad of emotional changes and challenges. The ability to identify, understand, and manage emotions also undergoes growth during this time. The component process approach highlights the significance of exposure to emotional antecedents, which shift during adolescence.

As adolescents grapple with new social situations, relationships, and expectations, they may experience increased stress. It is vital for them to develop appropriate coping mechanisms and emotional regulation skills to maintain their mental health. Support from family, friends, and educators can play a critical role in helping adolescents learn effective stress management techniques and emotional resilience.

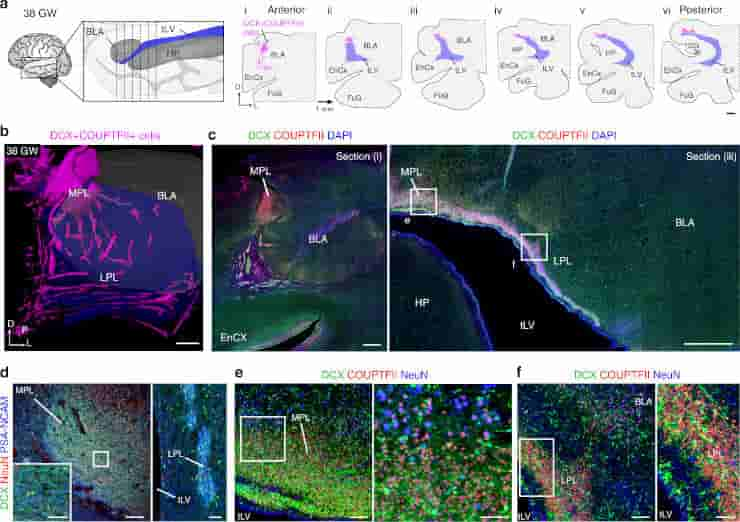

Researchers have uncovered a curious set of neurons in the amygdala, a critical site for emotional processing in the brain, that remain immature, prenatal developmental state throughout infancy. Most of these cells mature rapidly throughout adolescence, implying a function in emotional development in the brain, but some remain immature throughout life, suggesting novel theories about how the brain maintains its emotional responses’ flexibility throughout life.

Anyone who has been a teenager knows that they are going through a rapid and sometimes tumultuous emotional learning process about how to respond to stress, how to form positive social bonds, and so on.

A number of mental illnesses associated with the amygdala typically appear during adolescence, indicating that there may be a problem with the typical course of emotional and cognitive development. Whether or not this newly found group of neurons is involved will need to be investigated further.

Emotional Differentiation

There is evidence that adolescents are less able to discriminate between negative emotions than adults in their 20s and younger children. According to psychological scientist Erik Nook of Harvard University, children frequently report feeling only one emotion at a time, resulting in distinct yet limited emotional experiences. Adolescents begin to co-experience emotions but do not discriminate them well, whereas adults co-experience and differentiate emotions.

The influx of co-experienced emotions during adolescence may make this a time when emotions are more ambiguous, the results of a 2018 study that Nook was the lead author on suggests.

In the study, 143 participants aged 5 to 25 completed a series of emotion-related tasks. The researchers asked participants to define 27 different emotion terms in order to measure their grasp of different emotion terminologies. In a later emotion differentiation exercise, the researchers employed five of these emotion terms: angry, disgusted, sad, afraid, and upset.

Participants in this task examined a series of 20 photos depicting a negative scene of some kind. When seeing an image, participants reported how much they felt each of the five unpleasant emotions by sliding a bar on a scale to the appropriate amount (from 0 = not at all to 100 = very).

The results revealed a U-shaped pattern in participants’ experiences of negative emotions, with differentiation between emotions decreasing from childhood to adolescence and increasing again from adolescence to early adulthood.

“Adolescence is a period of heightened risk for the onset of psychopathology, and now we know that this is also a period when there’s less clarity in what one is feeling — something that lots of work has already connected to mental illness. We need to do a lot more work to draw a firm link between these two things, but it’s possible that increases in co-experienced emotions makes it more difficult for teens to differentiate and regulate their emotions, potentially contributing to risk of mental illness,”

Nook said.

Impact of Gender and Culture

Gender differences and cultural contexts are essential factors that influence emotional development during adolescence. Studies indicate that gender can affect adolescents’ emotional expression and stress management. For example, boys may be more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviours, while girls might report higher levels of emotional stress.

Cultural background also plays a role in shaping emotional development. Different cultural norms and expectations can impact adolescents’ emotional expression and coping strategies. It is crucial to consider these factors when providing support and guidance to adolescents, ensuring that their unique needs and experiences are taken into account.

Social and Emotional Challenges

Bullying is a significant issue for adolescents as they navigate the complexities of social life in school and online. Experiencing bullying can lead to various emotional and mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety.

Students often face peer pressure, which can exacerbate the negative impact of bullying. Some adolescents, for various reasons, are put in a position of having to care for younger siblings, or take other parental duties, a process called parentification. To counter these challenges, schools and families play a crucial role in teaching adolescents effective strategies for dealing with bullying and peer pressure.

Navigating Romantic Relationships and Sexuality

Adolescents often begin exploring their romantic relationships and sexuality during this stage of development. Navigating these experiences can be challenging and may increase the risk of emotional difficulties. Developing social and emotional competencies can contribute to positive relationship outcomes and help them make informed decisions in their romantic and sexual lives.

Dating during the adolescent years is regarded as a vital way for young people to establish self-identity, develop social skills, learn about other people, and emotionally grow. However, a 2019 study from the University of Georgia discovered that not dating can be an equally good option for teenagers. In some ways, these teenagers did even better.

The study found that adolescents who were not in romantic relationships during middle and high school had good social skills, lower levels of depression, and fared better or equal to peers who dated.

As stated by Brooke Douglas, the study’s principal author, the majority of teenagers have had some form of romantic experience by the age of 15 to 17 years old, or middle adolescence. Because of this high prevalence, some researchers believe that dating during adolescence is a normative activity. That is, adolescents who are in a romantic relationship are deemed to be ‘on time’ in their psychological development.

Does this mean that adolescents who do not date are maladjusted in some way? That they are social outcasts?

Not so, the data from the study said. Non-dating students exhibited equivalent or greater interpersonal skills than their dating peers. While the ratings for self-reported pleasant connections with friends, at home, and at school did not differ between dating and non-dating peers, teachers rated non-dating students much better for social skills and leadership skills than their dating classmates.

Students who did not date were also less likely to suffer from depression. Teachers’ depression scale scores were considerably lower in the group that reported no dating. Furthermore, the proportion of students who reported being unhappy or hopeless was much lower in this group.

The researchers concluded that non-dating students are doing well and simply follow a different and healthy developmental trajectory than their dating colleagues. The study refutes the notion of non-daters as social misfits.

Positive relationships of any kind contribute to healthy development by providing emotional support and fostering a sense of belonging. Strong connections with friends, family members, teachers, and mentors can help adolescents navigate social changes they face during this transitional period. Research has shown that positive relationships contribute to a reduction in emotional distress and improve social-emotional growth across adolescence.

Mental Health Issues

During adolescence, new brain networks come online, allowing teenagers to develop more complex adult social skills while potentially putting them at increased risk of mental illness. Teenagers are at an increased risk for various mental health difficulties, such as depression, anxiety, and other disorders.

Mental health problems often emerge during this transitional stage of social and emotional changes, with approximately 20% of adolescents experiencing a mental health issue at some point.

A team from the Universities of Cambridge and London published a major research study in 2020 that helps us understand the development of the adolescent brain more clearly.

The researchers gathered functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data on brain activity from 298 healthy young people aged 14 to 25 years, who were scanned one to three times roughly 6 to 12 months apart. Participants lay quietly in the scanner throughout each scanning session so that the researchers could examine the network of connections between different brain regions while the brain was at rest.

The team discovered that the functional connectivity of the human brain – in other words, how different regions of the brain ‘talk’ to each other – changes in two main ways during adolescence.

Credit: Nat Commun 10, 2748 (2019).

The brain regions responsible for vision, movement, and other basic faculties were closely linked by the age of 14 and became even stronger by the age of 25. This is known as a ‘conservative’ pattern of change, because parts of the brain that were densely connected at the onset of adolescence become even denser during the transition to adulthood.

However, brain regions essential to more advanced social skills, such as imagining what another person is thinking or feeling (so-called theory of mind), had a totally distinct pattern of change. Over the course of adolescence, connections in these regions were redistributed: connections that were initially weak became stronger, and connections that were initially strong became weaker.

This was called a ‘disruptive’ pattern of change, as areas that were poor in their connections became richer, and areas that were rich became poorer.

By comparing the fMRI results to other brain data, the researchers discovered that the network of regions that displayed the disruptive pattern of change during adolescence had high levels of metabolic activity, which is typically associated with active re-modelling of nerve cell connections.

These findings indicate that active re-modelling of brain networks occurs during the adolescent years, and a better understanding of brain development may lead to a better understanding of the causes of mental illness in adolescence.

References:

- Aviles, A.M., Anderson, T.R. and Davila, E.R. (2006), Child and Adolescent Social-Emotional Development Within the Context of School. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 11: 32-39

- Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., & Tsai, J. L. (2007). Gender differences in emotional response among European Americans and Hmong Americans. Cognition and Emotion, 21(1), 162–181

- Crockett, Lisa; Losoff, Mike; Petersen, Anne C. (1984). Perceptions of the Peer Group and Friendship in Early Adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 4 (2): 155–181. doi:10.1177/0272431684042004

- Douglas, B., & Orpinas, P. (2019). Social Misfit or Normal Development? Students Who Do Not Date. The Journal of school health, 89(10), 783–790.

- McLaughlin, Katie A et al. What develops during emotional development? A component process approach to identifying sources of psychopathology risk in adolescence. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience vol. 17,4 (2015): 403-10. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.4/kmclaughlin

- Nook EC, Sasse SF, Lambert HK, McLaughlin KA, Somerville LH. The Nonlinear Development of Emotion Differentiation: Granular Emotional Experience Is Low in Adolescence. Psychol Sci. 2018 Aug;29(8):1346-1357. doi: 10.1177/0956797618773357

- Roeser, Robert & Eccles, Jacquelynne & Sameroff, Arnold. (2000). School as a Context of Early Adolescents’ Academic and Social-Emotional Development: A Summary of Research Findings. The Elementary School Journal. 100. 443-471. 10.1086/499650.

- Shawn F. Sorrells, Mercedes F. Paredes, Dmitry Velmeshev, Vicente Herranz-Pérez, Kadellyn Sandoval, Simone Mayer, Edward F. Chang, Ricardo Insausti, Arnold R. Kriegstein, John L. Rubenstein, Jose Manuel Garcia-Verdugo, Eric J. Huang, Arturo Alvarez-Buylla. Immature excitatory neurons develop during adolescence in the human amygdala. Nature Communications, 2019; 10 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-10765-1

- Váša, F., Romero-Garcia, R., Kitzbichler, M. G., Seidlitz, J., Whitaker, K. J., Vaghi, M. M., Kundu, P., Patel, A. X., Fonagy, P., Dolan, R. J., Jones, P. B., Goodyer, I. M., NSPN Consortium, Vértes, P. E., & Bullmore, E. T. (2020). Conservative and disruptive modes of adolescent change in human brain functional connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(6), 3248–3253.