Researchers have found a previously unidentified area of brain anatomy that serves as a barrier of defense and a base from which immune cells watch the brain for inflammation and infection.

The human brain only reluctantly divulges its secrets, including the intricate nature of neural networks and fundamental biological processes and structures. Only recently have developments in molecular biology and neuroimaging made it possible for researchers to study the living brain in great detail, solving many of its mysteries.

“The discovery of a new anatomic structure that segregates and helps control the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in and around the brain now provides us much greater appreciation of the sophisticated role that CSF plays not only in transporting and removing waste from the brain, but also in supporting its immune defenses,”

said Maiken Nedergaard, co-director of the Center for Translational Neuromedicine at the Universities of Rochester and Copenhagen.

The new research was conducted in the labs of Nedergaard and Kjeld Mllgrd, a professor of neuroanatomy at the University of Copenhagen.

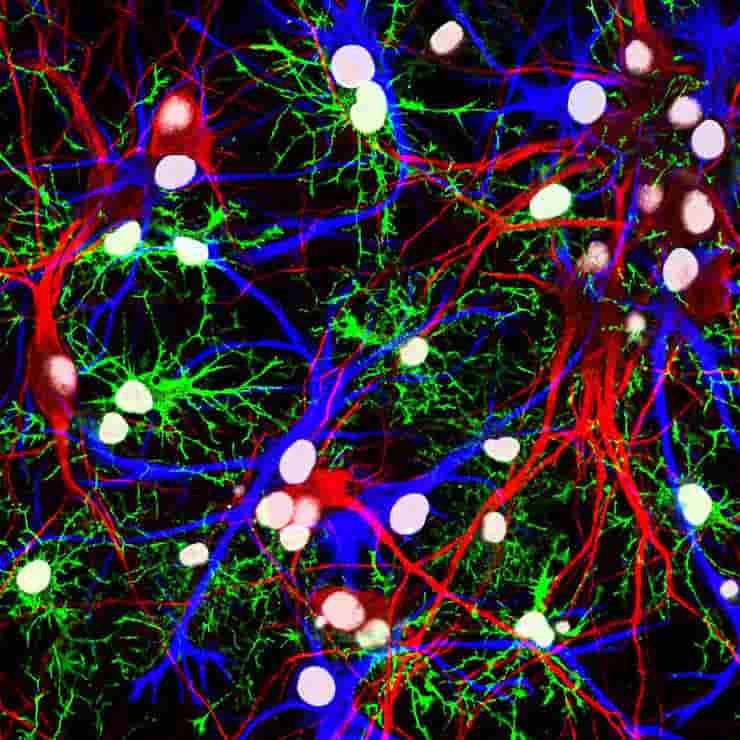

Subarachnoidal Lymphatic-like Membrane

Credit: NICHD/J. Cohen

Nedergaard and her colleagues have changed the way we think about how the brain works and made important contributions to the field of neuroscience. For example, they have helped us understand the many essential functions of brain cells called glia and the brain’s unique system for getting rid of waste, which they named the glymphatic system.

This most recent study focuses on the series of membranes that encase the brain, forming a barrier from the rest of the body and ensuring that the brain is constantly bathed in cerebrospinal fluid. Traditionally, dura, arachnoid, and pia matter are thought to be the three separate layers that make up what is called the meningeal layer.

The new layer discovered by the researchers from the United States and Denmark divides the space between the arachnoid and pia layers, known as the subarachnoid space, into two compartments, separated by the newly described layer, which the researchers call SLYM, an abbreviation for Subarachnoidal LYmphatic-like Membrane.

Thin But Strict Barrier

While a large portion of the research in the paper discusses SLYM’s role in mice, they also report that it is present in the adult human brain.

The subarachnoidal lymphatic-like membrane is a type of membrane called mesothelium that lines other organs, including the lungs and heart. Typically, these membranes surround and protect organs and house immune cells.

The first author of the study, Møllgård, whose research focuses on developmental neurobiology and on the systems of barriers that protect the brain, was the one who first raised the possibility that a similar membrane might exist in the central nervous system.

Only a few cells make up the new membrane, which is highly fragile and thin. However, SLYM is a strict barrier that only lets through very small molecules, and it also appears to distinguish between “clean” and “dirty” cerebrospinal fluid.

This last point suggests that SLYM may play a role in the glymphatic system, which requires a controlled flow and exchange of CSF, allowing fresh CSF to enter while flushing toxic proteins associated with Alzheimer’s and other neurological diseases from the central nervous system. So this discovery will aid researchers in better understanding the glymphatic system’s mechanics.

Brain Immune Defense

The subarachnoidal lymphatic-like membrane appears to be important in the brain’s defenses as well. The central nervous system has its own native immune cell population, and the integrity of the membrane prevents outside immune cells from entering.

Furthermore, the membrane appears to support its own population of central nervous system immune cells, which use SLYM as a point of observation close to the brain’s surface from which to scan passing CSF for signs of infection or inflammation.

The discovery of the SLYM allows for more research into its role in brain disease. For example, during inflammation and aging, larger and more diverse concentrations of immune cells congregate on the membrane.

In addition, when the membrane was ruptured during traumatic brain injury, the disruption in CSF flow weakened the glymphatic system and allowed immune cells from the peripheral nervous system to enter the brain.

These and other findings suggest that abnormalities in SLYM function may cause or worsen diseases as diverse as multiple sclerosis, central nervous system infections, and Alzheimer’s.

They also suggest that SLYM might make it harder for medicines and gene therapies to reach the brain. This is something that will need to be taken into account as new generations of biologic therapies are created.

The study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Lundbeck Foundation, the Human Frontier Science Program, Novo Nordisk Foundation, the US Army Research Office, the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and the Simons Foundation.

Reference:

- Kjeld Møllgård, Felix R. M. Beinlich, Peter Kusk, Leo M. Miyakoshi, Christine Delle, Virginia Plá, Natalie L. Hauglund, Tina Esmail, Martin K. Rasmussen, Ryszard S. Gomolka, Yuki Mori and Maiken Nedergaard. A mesothelium divides the subarachnoid space into functional compartments. Science, Volume 379, Issue 6627 DOI: 10.1126/science.adc8