Researchers looked into the overlapping and distinct neural processes that underlie general semantic, personal semantic, and episodic long-term memory. The study suggests that these memory types all use the same network of the brain, rather than relying on different areas of the brain altogether.

This puts into doubt a previous hypothesis that distinguished between general semantic and episodic memory. Instead, the authors propose that different types of long-term memory could be understood as a spectrum, with varied degrees of activation in the same parts of the brain.

Memory Categories

Long-term memory can be divided into several categories. The contrast between semantic and episodic memory is one of the most common.

While episodic memory pertains to the recollection of situationally specific events from one’s personal history, semantic memory pertains to an individual’s general, non-personal knowledge of the world.

For instance, the thought “I know that a sauna is very hot, steamy, and relaxing ” is an example of a semantic memory, while “I remember winning a dare of who could stay longest in the sauna. It was a Friday night and we celebrated with a large glass of cucumber water,” is an example of episodic memory.

Personal Semantic Memory

In recent years, this distinction has been called into question. Previous studies found a link between the neural correlates of semantic and episodic memory.

Neural correlates refer to the specific patterns of brain activity that are associated with the creation, storage and/or retrieval of memories and are used to help researchers understand how memories are formed and accessed in the brain. Moreover, the semantic-episodic distinction does not neatly account for a number of long-term memory types.

For example, personal semantics includes knowledge of personal facts (for example, “I have a sauna membership”) and summaries of repeated events (for example, “I always start my gym routine with stretches and good music”).

Therefore, in a conceptual sense, personal semantics is situated in the intermediate realm between semantic and episodic memory; similar to episodic memories, it is personal, yet distinct from the specific circumstances surrounding its acquisition, as is the case with semantic memories.

Understudied Long-term Memory Area

While neural correlates for certain types of personal semantics, such as autobiographical facts, resemble those of semantic memory, those for episodic memory are more akin to those found in memories of repeated events.

“Personal semantics, despite its importance, remains an understudied area of long-term memory,”

said lead author Annick Tanguay, who conducted the study at the School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, and the University of East Anglia, Norwich. Tanguay is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“Few studies have directly compared personal semantics to semantic or episodic memory, and even fewer have compared different types of personal semantics to one another or to both semantic and episodic memory. With our study, we were able to do so,”

added senior author Patrick Davidson, Associate Professor at the School of Psychology, University of Ottawa.

Shared Core Memory Network

Tanguay and colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to record the brain activity of 48 participants while they answered yes/no questions about memory for general knowledge (semantic memory), unique events (episodic memory), autobiographical knowledge, or memory for repeated events (two types of personal semantic memory). The researchers then employed multivariate analysis methods to compare the subjects’ brain activity across the four memory circumstances.

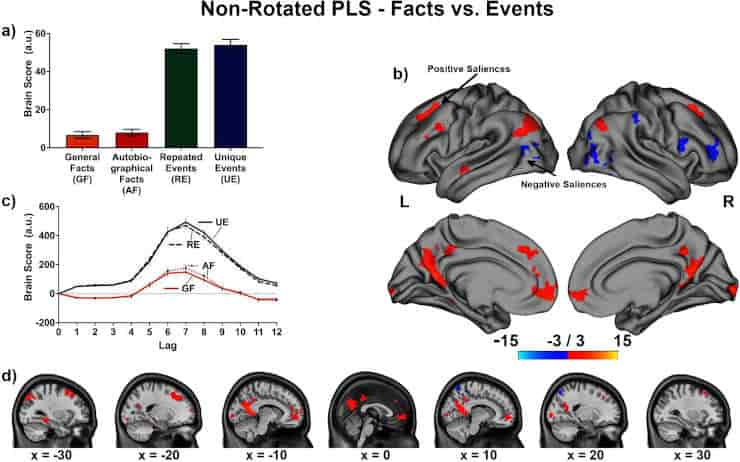

Their results indicated that personal semantic, general semantic and episodic memory had both shared and unique neural correlates.

When they compared four memory conditions — autobiographical facts, repeated events, general semantics, and episodic memory — with a control condition, they observed that all four types of memory involved activity in several regions of the brain’s “core memory network.”

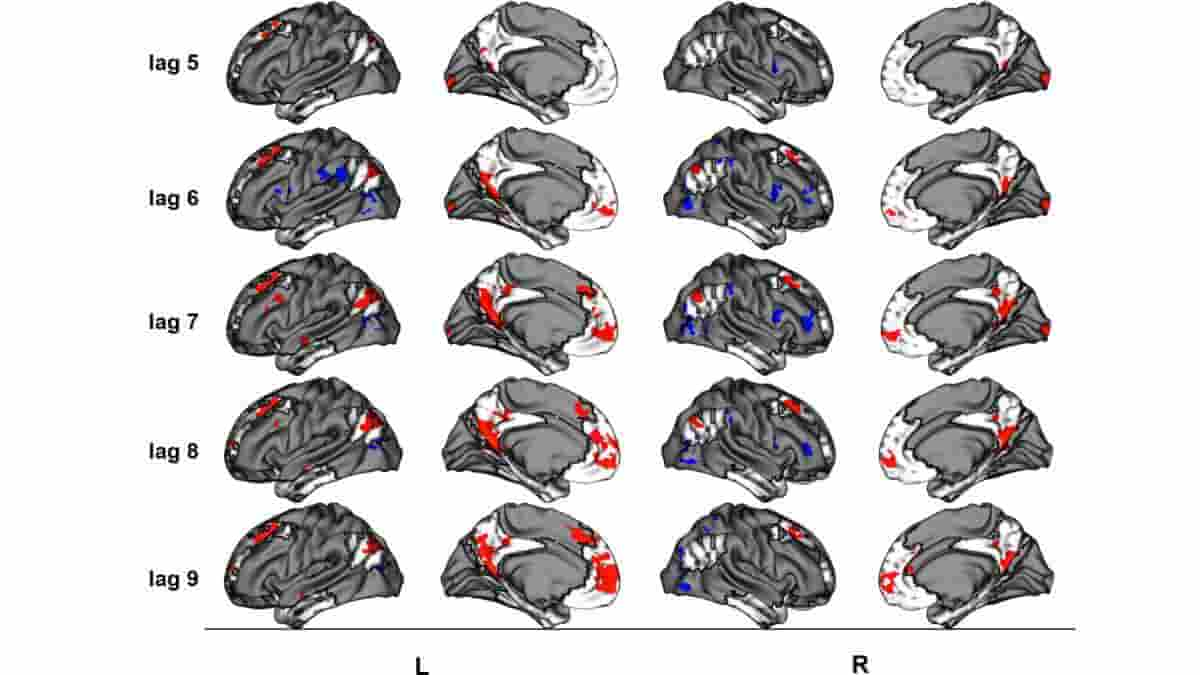

When the researchers analyzed the four memory circumstances independently, they discovered that they each activated the network to a different degree of scale. When comparing autobiographical information to general knowledge facts, there was a relatively minor increase in activity in the vast regions of the brain’s medial frontal cortex, posterior parietal cortex, and medial temporal lobes.

There was a further, larger increase in activity when remembering repeated events and another small increase when remembering unique events. In other areas of the brain, such as the right frontal inferior gyrus and the superior parietal lobule, the team also observed a progressive decrease in activity in the same order of memory types.

Similarities and Differences

Another 106 participants made ratings on the same statements to gain additional insights into what might explain similarities and differences between memory types.

In summary, brain activity in several regions of the “core memory network” seemed to match up with an increase in personal relevance, an increase in the visual details people observed in their minds’ eye, and whether the memory featured a scene. The authors caution, however, about drawing comparisons based on data from different groups of participants.

“Rather than looking at a memory type overall, more work needs to be done to understand links between individual pieces of information across the spectrum of memory. For example, what does it mean for someone to know they usually do stretches at the gym and also to remember a specific instance when this happened?”

commented co-author Daniela Palombo, Associate Professor at the Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia.

“Taken together, our data support a continuum perspective of long-term memory, with different memory types varying in magnitude of activation within a common network of brain regions,”

concluded senior author Louis Renoult, associate professor in psychology at the School of Psychology, University of East Anglia.

Future research could focus on better understanding the nature of the fundamental components that underpin the similarities and differences between these memory types, such as the perceptual and spatial aspects of these memories and the amount of self-reflection involved.

Abstract

One of the most common distinctions in long-term memory is that between semantic (i.e., general world knowledge) and episodic (i.e., recollection of contextually specific events from one’s past). However, emerging cognitive neuroscience data suggest a surprisingly large overlap between the neural correlates of semantic and episodic memory. Moreover, personal semantic memories (i.e., knowledge about the self and one’s life) have been studied little and do not easily fit into the standard semantic-episodic dichotomy. Here, we used fMRI to record brain activity while 48 participants verified statements concerning general facts, autobiographical facts, repeated events, and unique events. In multivariate analysis, all four types of memory involved activity within a common network bilaterally (e.g., frontal pole, paracingulate gyrus, medial frontal cortex, middle/superior temporal gyrus, precuneus, posterior cingulate, angular gyrus) and some areas of the medial temporal lobe. Yet the four memory types differentially engaged this network, increasing in activity from general to autobiographical facts, from autobiographical facts to repeated events, and from repeated to unique events. Our data are compatible with a component process model, in which declarative memory types rely on different weightings of the same elementary processes, such as perceptual imagery, spatial features, and self-reflection.

Reference:

- Annick FN Tanguay, Daniela J Palombo, Brittany Love, Rafael Glikstein, Patrick SR Davidson, Louis Renoult (2023) The shared and unique neural correlates of personal semantic, general semantic, and episodic memory. eLife 12:e83645

Last Updated on January 6, 2024