Researchers in the field of neuroscience have found an interesting link between being able to remember things from your childhood and the way brains develop in people with autism.

Most of us have little recollection of our lives prior to the age of two. The term infantile amnesia refers to this seeming complete loss of episodic and autobiographical memories generated throughout childhood.

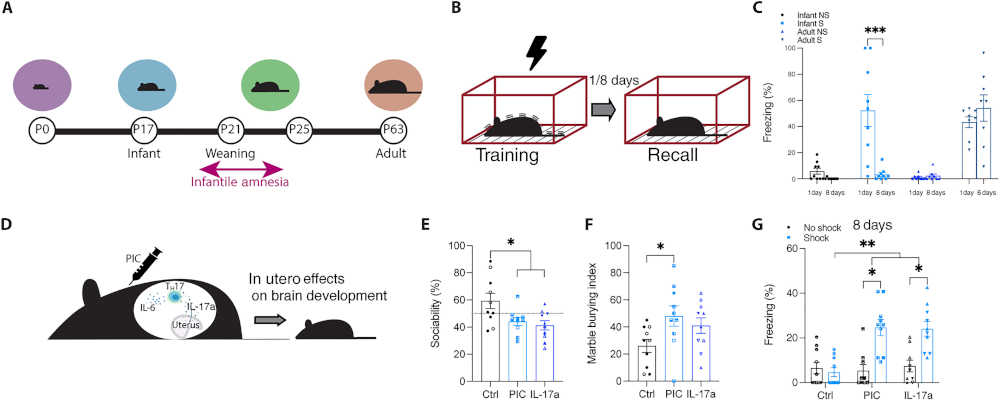

The maternal immune response, which is activated in response to infection during pregnancy, has been linked to autism in both humans and mice. Trinity College Dublin neuroscientists now report for the first time that this altered brain state also prevents the usual loss of memories formed during infancy.

Maternal Immune Activation

Researchers used a mouse model to find that maternal immune activation, which is when inflammation is artificially induced during pregnancy without an infection in order to change the brain development of the child, protects against developmental memory loss in childhood by changing how brain cells that store memories (engrams) work.

Credit: Sci. Adv. 9, eadg9921 (2023) DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adg9921

Furthermore, the study found that if the correct memory engrams are activated in adults, memories that were previously forgotten can be permanently reinstated. In these experiments, they used a optogenetics approach, which uses light to trigger specific neural pathways linked to the memory engrams of interest.

These findings suggest that infantile amnesia is caused by a retrieval deficit, as early childhood memories are still retained in the adult brain but cannot be accessed normally by natural recollection.

Widespread Relevance

The article’s senior author is Dr. Tomás Ryan, Associate Professor in Trinity’s School of Biochemistry and Immunology and the Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience.

“Infantile amnesia is possibly the most ubiquitous yet underappreciated form of memory loss in humans and mammals. Despite its widespread relevance, little is known about the biological conditions underpinning this amnesia and its effect on the engram cells that encode each memory. As a society, we assume infant forgetting is an unavoidable fact of life, so we pay little attention to it,”

said Dr. Ryan, noting the significance of these findings.

These new findings suggest that immunological stimulation during pregnancy modifies our intrinsic, yet reversible, ‘forgetting switches,’ which decide whether or not baby memories are forgotten. The study also has important implications for improving our understanding of memory and forgetting throughout infant development, as well as overall cognitive flexibility in the context of autism.

“Our brains’ early developmental trajectories seem to affect what we remember or forget as we move through infancy. We now hope to investigate in more detail how development affects the storage and retrieval of early childhood memories, which could have a number of important knock-on impacts from both an educational and a medical perspective,”

said the lead author of the study, Dr. Sarah Power.

This study marks a significant milestone in developmental memory research by shedding insight on the relationship between early childhood memory retention and maternal immune responses linked with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). It also emphasizes brain function’s plasticity in response to environmental stimuli during embryonic and early postnatal development.

Abstract

Infantile amnesia is possibly the most ubiquitous form of memory loss in mammals. We investigated how memories are stored in the brain throughout development by integrating engram labeling technology with mouse models of infantile amnesia. Here, we found a phenomenon in which male offspring in maternal immune activation models of autism spectrum disorder do not experience infantile amnesia. Maternal immune activation altered engram ensemble size and dendritic spine plasticity. We rescued the same apparently forgotten infantile memories in neurotypical mice by optogenetically reactivating dentate gyrus engram cells labeled during complex experiences in infancy. Furthermore, we permanently reinstated lost infantile memories by artificially updating the memory engram, demonstrating that infantile amnesia is a reversible process. Our findings suggest not only that infantile amnesia is due to a reversible retrieval deficit in engram expression but also that immune activation during development modulates innate, and reversible, forgetting switches that determine whether infantile amnesia will occur.

Reference:

- Sarah D. Power et al. Immune activation state modulates infant engram expression across development. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg9921 (2023) DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adg9921

Last Updated on December 27, 2023