The benefits of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) are maximized, according to new research, through the use of a combination of cognitive and behavioral strategies, optimally administered in person by a therapist. CBT-I, a variant of talk therapy, may be administered via self-help manuals or in-person sessions.

Through the examination of 241 studies encompassing more than 30,000 adults, scholars discerned the most advantageous elements of CBT-I. In-person delivery, cognitive restructuring, third-wave components, sleep restriction, and stimulus control were among these.

Self-help accompanied by human encouragement may also yield positive outcomes, whereas relying on active treatment and imposing relaxation techniques seem to have the potential to cause damage. By identifying the most beneficial components of CBT-I, practitioners will presumably be in a better position to assist their patients in achieving a more restful night’s sleep.

Insomnia in Adults

Even though it is bedtime, your thoughts are rushing. Perhaps you awaken multiple times throughout the night or feel extremely unrested when you awaken early in the morning. There are estimates that as many as one-third of adults, and between 4% and 22% chronically, suffer from insomnia at some stage in their lives.

The effects of chronic insomnia on daily life can be distressing or incapacitating, making it difficult to function when alert. More severe cases may necessitate support and treatment, and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia is one option without the use of medication.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia is a form of therapy that uses educational, cognitive or behavioral strategies to help patients improve their quality of sleep. It may be delivered in person or online, through an app or a guidebook, with the support of a therapist or independently.

CBT-I has been demonstrated to be a beneficial and low-risk option for patients with chronic insomnia in prior research. As it incorporates a wide variety of strategies that may be implemented in various ways, it has proven challenging to ascertain which are the most effective and whether or not all are required for a patient to observe an improvement.

Cognitive Component Benefits

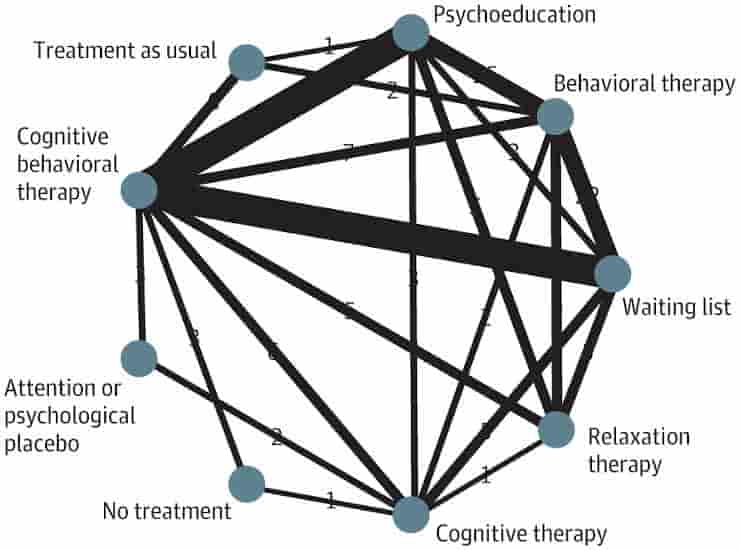

Credit: JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5060

241 studies of chronic insomnia from 1980 to 2023 were analyzed by a team led by researchers at the University of Tokyo Hospital in an effort to establish a correlation between the various tenets of CBT-I and their outcomes. The research investigations encompassed 31,452 adult subjects, predominantly hailing from Europe and North America, and averaging 45.4 years of age.

“We expected to find some behavioral components (such as sleep restriction and stimulus control) beneficial, but it was surprising to find that some cognitive components (such as cognitive restructuring and third-wave components) were also effective,”

explained Yuki Furukawa, lead author and a medical doctor at the university hospital.

By employing component network meta-analysis, a statistical technique, the group assessed and ranked the impacts of various interventions. While engaging in a self-help program with the support of others proved to be beneficial, the results indicated that face-to-face counseling provided greater advantages.

Other critical components included: cognitive restructuring (skills to identify, challenge and change unhelpful beliefs about sleep), sleep restriction (limiting time in bed), stimulus control (re-associating bed with sleep) and third-wave components (mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy).

Detrimental and Futile Techniques

However, it did not seem that sleep hygiene education, which encompasses explanations of the biological aspects of sleep as well as recommendations regarding one’s lifestyle and environment, was crucial. Attempting to adhere to relaxation techniques (such as structured cognitive or physical exercises) may prove futile, whereas being required to wait for therapy to commence appeared to have a detrimental impact.

“Overall, our findings identified several essential components of CBT-I which can lead to an intervention that maximizes treatment efficacy, minimizes treatment burden and increases scalability, that is, makes it easier to offer this treatment to more patients. Further large-scale trials are needed to confirm these contributions,”

said Furukawa.

The researchers hope that their findings will encourage practitioners who are interested in CBT-I to learn streamlined CBT-I, allowing more people suffering from insomnia to receive this relatively simple, noninvasive, yet potentially powerful psychotherapy.

Abstract

Importance: Chronic insomnia disorder is highly prevalent, disabling, and costly. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), comprising various educational, cognitive, and behavioral strategies delivered in various formats, is the recommended first-line treatment, but the effect of each component and delivery method remains unclear.

Objective: To examine the association of each component and delivery format of CBT-I with outcomes.

Data Sources: PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PsycInfo, and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform from database inception to July 21, 2023.

Study Selection: Published randomized clinical trials comparing any form of CBT-I against another or a control condition for chronic insomnia disorder in adults aged 18 years and older. Insomnia both with and without comorbidities was included. Concomitant treatments were allowed if equally distributed among arms.

Data Extraction and Synthesis: Two independent reviewers identified components, extracted data, and assessed trial quality. Random-effects component network meta-analyses were performed.

Main Outcomes and Measures: The primary outcome was treatment efficacy (remission defined as reaching a satisfactory state) posttreatment. Secondary outcomes included all-cause dropout, self-reported sleep continuity, and long-term remission.

Results: A total of 241 trials were identified including 31 452 participants (mean [SD] age, 45.4 [16.6] years; 21 048 of 31 452 [67%] women). Results suggested that critical components of CBT-I are cognitive restructuring (remission incremental odds ratio [iOR], 1.68; 95% CI, 1.28-2.20) third-wave components (iOR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.10-2.03), sleep restriction (iOR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.04-2.13), and stimulus control (iOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.00-2.05). Sleep hygiene education was not essential (iOR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.77-1.32), and relaxation procedures were found to be potentially counterproductive(iOR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.64-1.02). In-person therapist-led programs were most beneficial (iOR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.19-2.81). Cognitive restructuring, third-wave components, and in-person delivery were mainly associated with improved subjective sleep quality. Sleep restriction was associated with improved subjective sleep quality, sleep efficiency, and wake after sleep onset, and stimulus control with improved subjective sleep quality, sleep efficiency, and sleep latency. The most efficacious combination—consisting of cognitive restructuring, third wave, sleep restriction, and stimulus control in the in-person format—compared with in-person psychoeducation, was associated with an increase in the remission rate by a risk difference of 0.33 (95% CI, 0.23-0.43) and a number needed to treat of 3.0 (95% CI, 2.3-4.3), given the median observed control event rate of 0.14.

Conclusions and Relevance: The findings suggest that beneficial CBT-I packages may include cognitive restructuring, third-wave components, sleep restriction, stimulus control, and in-person delivery but not relaxation. However, potential undetected interactions could undermine the conclusions. Further large-scale, well-designed trials are warranted to confirm the contribution of different treatment components in CBT-I.

Reference:

- Furukawa Y, Sakata M, Yamamoto R, et al. Components and Delivery Formats of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Insomnia in Adults: A Systematic Review and Component Network Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online January 17, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5060

Last Updated on February 8, 2024