Researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science have discovered in unprecedented detail how the brains of male and female mice react differently to stress. The findings may lead to a better understanding of health conditions affected by chronic stress, such as anxiety, depression, and even obesity and diabetes, and pave the way for personalized treatments for these disorders.

The study conducted by researchers from the joint laboratory of Prof. Alon Chen at the Weizmann Institute and the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich revealed that a specific subset of brain cells exhibits distinct responses to chronic stress in males versus females.

Scientific excellence necessitates diversity: research undertaken by men and women, as well as people from various origins and with diverse worldviews. The need for diversity extends to scientific experiments, but even today, the vast majority of studies in the life sciences are conducted on male mice only, which may harm the findings as well as our ability to extrapolate from them to humans.

Chronic Stress On the Rise

Chronic stress-related mental and physical diseases are on the rise, putting considerable pressure on society. They have an impact on both men and women, but not always in the same way.

Although there is plenty of evidence that men and women deal with stress differently, the origins of these differences are not fully understood, and individualized treatments for men and women are currently out of reach for medicine. However, researchers from Chen’s laboratory, which specializes in stress research, speculated that novel research methodologies could assist in modifying the picture.

Previous research in other labs had discovered certain sex differences in the response to stress, but those findings were obtained using research methods that could mask significant differences in the responses of specific cells or even completely erase the roles played by relatively rare cells.

Chen’s laboratory, on the other hand, employs cutting-edge techniques that allow scientists to analyze brain activity at unprecedented resolution – on the level of individual cells – and may shed new light on gender differences.

“We turned the most sensitive research lens possible onto the area of the brain that acts as a central hub of the stress response in mammals, the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus,”

said Dr. Elena Brivio, who led the study.

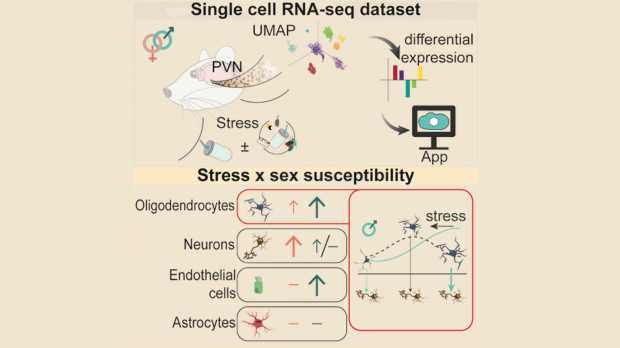

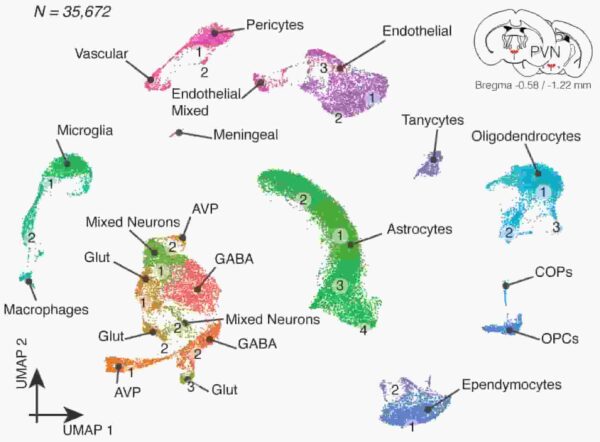

Paraventricular Nucleus RNA

The researchers were able to map the stress response in male and female mice along three main axes by sequencing the RNA molecules in the hypothalamus paraventricular nucleus at the individual cell level: how each cell type in that part of the brain responds to stress, how each cell type previously exposed to chronic stress responds to a new stress experience, and how these responses differ between males and females.

Credit: Cell Reports, 2023; 42 (8): 112874 DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112874 CC-BY

The researchers mapped gene expression in over 35,000 individual cells, generating a massive amount of data that provides an unprecedented picture of stress response, highlighting differences between how males and females perceive and process stress.

As part of the study, and in accordance with open-access science principles, the researchers decided to make the entire detailed mapping publicly available on a dedicated interactive website, which went live at the same time the study was published, allowing other researchers convenient, user-friendly access to the data.

“The website will, for example, allow researchers who are focusing on a specific gene to see how that gene’s expression changes in a certain cell type in response to stress, in males as well as females,”

Brivio explained.

Oligodendrocyte Changes

The extensive mapping has already enabled the researchers to find a plethora of changes in gene expression between males and females, as well as between chronic and acute stress. The findings revealed, among other things, that particular brain cells in males and females respond differently to stress.

Certain cells exhibit differential susceptibility to stress in females and males. The most notable disparity was observed in the oligodendrocyte, a specific type of glial cell responsible for providing structural support to neurons and contributing to the modulation of brain function.

Stress, particularly chronic stress, altered not just the gene expression in these cells and their connections with adjacent nerve cells in males, but also their physical shape. Females, on the other hand, showed no significant alteration in these cells and were not responsive to stress exposure.

“Neurons attract most of the scientific attention, but they only make up approximately a third of all cells in the brain. The method we implemented allows us to see a much richer and fuller picture, including all the cell types and their interactions in the part of the brain under study,”

said Dr. Juan Pablo Lopez, a former postdoctoral fellow in Chen’s group, now at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

Diversity in Basic Research

Until the 1980s, clinical trials of new drugs were conducted on men alone. The accepted view was that including women was unnecessary and that it would only complicate the research, bringing into play new variables such as menstruation and hormonal changes.

Until recently, preclinical research avoided utilizing female animals for the same reasons. However, it is now recognized that male animals have greater variety on a biochemical and behavioural level than females, so there is no reason to believe that females would complicate the tests any more than males.

Nonetheless, it is still common in basic research to conduct experiments on only men.

“Our findings show that, when it comes to stress-related health conditions, from depression to diabetes, it’s very important to take the sex variable into account, since it has a significant impact on how different brain cells respond to stress,”

Chen said.

“Even if a study does not specifically focus on the differences between males and females, it’s essential to include female animals in the research, especially in neuroscience and behavioral science, just as it is important to implement the most sensitive research methods, in order to obtain as complete a picture of brain activity as possible,”

Brivio added.

Reference:

- Elena Brivio, Aron Kos, Alessandro Francesco Ulivi, Stoyo Karamihalev, Andrea Ressle, Rainer Stoffel, Dana Hirsch, Gil Stelzer, Mathias V. Schmidt, Juan Pablo Lopez, Alon Chen. Sex shapes cell-type-specific transcriptional signatures of stress exposure in the mouse hypothalamus. Cell Reports, 2023; 42 (8): 112874 DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112874