Children who have experienced the death of a loved one will benefit from learning more about why and how people die and how to make sense of this, according to new research led by Curtin University.

The study asked 220 bereaved children between the ages of 5 and 12 who attended one of ten Lionheart Camps for Kids to submit questions about death and grief in order to better comprehend their curiosity and emotions regarding these significant life events and transitions.

Children were particularly interested in why and how people die, how death can be prevented or delayed, how to make sense of death, understanding and managing grief, understanding life and death, how medical interventions work, and what happens after you die, according to the research.

Bereaved Children and Mental Health Risk

Lead researcher Professor Lauren Breen, from the Curtin School of Population Health, said the children’s questions in this study offered important insights into their thoughts and feelings, as well as their curiosity about death following the loss of a loved one.

“Approximately 5% to 7% of children in Western countries will experience the death of a parent or sibling before the age of 18, increasing to 50% when including the loss of a close family member or friend. Bereaved children are also at a higher risk of developing anxiety, depression, poor academic performance, suicidal thoughts and engaging in substance use,”

Professor Breen said.

“These statistics are alarming and have only increased following the rise of COVID-19, where an estimated 1.1 million children worldwide experienced the death of a parent in the first 14 months of the pandemic,”

he added.

Lots of Questions

It is crucial to ensure that effective and appropriate strategies, such as camps like Lionheart Camp for Kids, are in place to support grieving children, and that parents have the best resources to help them cope with the loss of a loved one.

The study was able to demonstrate that children who are experiencing the death of a loved one are curious about death and may wish to discuss their emotions and ask questions to better comprehend why a loved one is no longer with them and how they can best adjust to this significant life change.

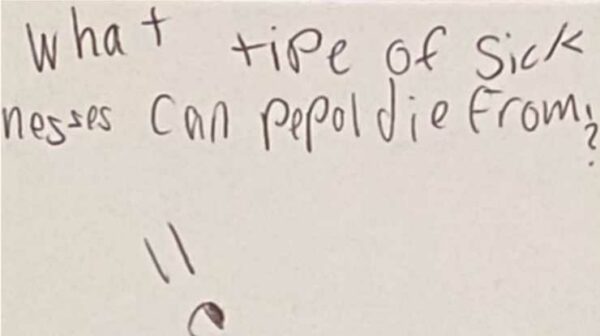

Some of the questions asked by children included:

- Why did he leave me?

- How does the body actually die?

- Why do kids bully me at school now?

- What type of sicknesses can people die from?

- How does a pacemaker work?

- What is the meaning of life?

- What does it feel like to be in heaven?

Professor Breen explained that a significant amount of the information provided to grieving children by health professionals and in school is based on their age and level of development; however, it may be more appropriate to base these decisions on the child’s level of curiosity and comprehension.

Challenging for Many Adults

It is critical to provide adequate support for grieving children in order to help them manage their emotions, process their grief, and develop coping skills that will help them navigate the next stages of life.

“It is very challenging for many adults to openly discuss grief with their children when they are also experiencing the same grief and loss. Our research shows that instead of shielding children which may be the natural instinct, it may be more beneficial for caregivers who are anticipating a death of a loved one to have open discussions with their children about what is happening and what this means for them,”

Breen said.

More research is needed to better understand the mourning children’s experiences and viewpoints. Understanding this allows for more appropriate methods to be put in place to provide the appropriate level of support in a safe setting.

“This study shows that support services may benefit from considering not just what children need to know, but what they want to know about death and grief,”

he said.

According to Lionheart Camp for Kids CEO and Founder Shelly Skinner, adults are often awkward when discussing death and grief, whereas children are curious and have both general and in-depth questions about illness, the physical process of dying, what it feels like to die, and what happens after we die.

Limitations

The study does have some limitations. Because the data was collected anonymously, the team was unable to compare questions based on demographic details such as age, gender, race, religion, or culture, which are likely critical to our understanding of what bereaved children need.

Likewise, they were unable to compare questions based on children’s relationship with the deceased (e.g., parent compared to sibling), the manner of death (e.g., terminal illness compared to suicide), and time since the loss (e.g., one month compared to one year ago). Such information could offer insight into children’s needs at varying stages of their bereavement experience, depending on who died and how.

Future research on bereaved children’s questions should account for these details to strengthen our understanding of what children want to know about death and grief, and improve the bereavement supports designed for them.

“While the aim of this study was to categorize the questions bereaved children ask about death and grief, the nature of the data means that only a conceptual understanding of children’s questions can be gained. In absence of data related to children’s lived experiences and the context of their questions, the present research cannot offer a nuanced picture of what children want to know about death and grief. For example, we are unable to determine whether children only asked questions related to the death of their own loved one, or if their questions advanced beyond their direct experience and reflected things they had been exposed to at camp. Given that children hear about each other’s bereavement experiences during the camp, their questions may capture not just their own experiences but those of other children as well. Future research might catalog children’s questions over time to examine temporal changes in their questions,”

the authors wrote.

Finally, while the children’s inquiries fit the current understanding of children’s death concepts, it’s probable that the emphasis on medical and biological features arose because the children knew a medical practitioner would answer their questions. Different questions may have been posed if questions were answered by a different expert (e.g., psychologist, teacher, somebody with lived experience).

Future research could look into the impact of different sorts of experts on children’s queries, which could be valuable for directing more particular preparation to individuals who work with grieving children.

Abstract

While childhood bereavement is common, children’s bereavement needs are not well understood. It is recognized that children’s understandings of death fundamentally differ from those of adults, however, limited research has explored this from a child’s perspective. Insight about children’s understandings and needs can be drawn from the questions they ask about it. Bereaved children aged 5–12 years were invited to submit questions about death and grief during a camp for grieving children. Children’s questions (N = 213) from 10 camps were analyzed using conventional content analysis. Five themes were identified: Causes and Processes of Death; Human Intervention; Managing Grief; The Meaning of Life and Death; and After Death. Children’s questions revealed that they are curious about various biological, emotional, and existential experiences and concepts, demonstrating complex and multi-faceted considerations of death and its subsequent impact on their lives. Findings suggest that bereaved children may benefit from opportunities to freely discuss their thoughts about death, which may facilitate appropriate education and emotional support.

Reference:

- Joy, C., Staniland, L., Mazzucchelli, T.G. et al. What Bereaved Children Want to Know About Death and Grief. J Child Fam Stud (2023). doi: 10.1007/s10826-023-02694-x