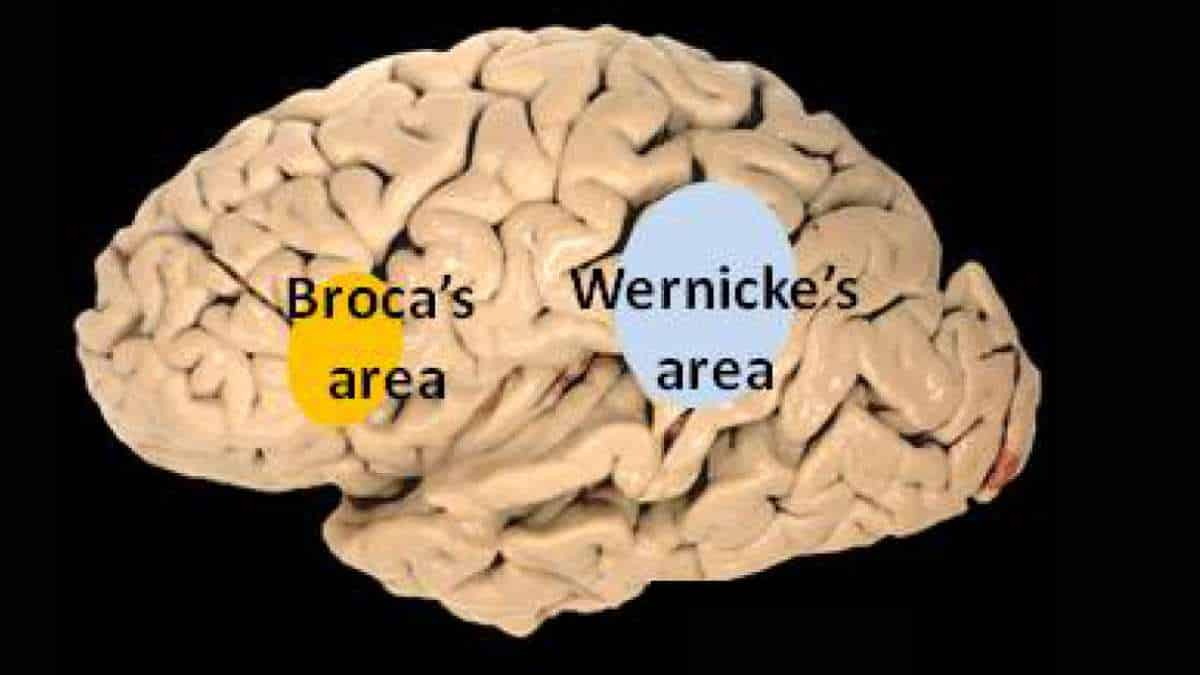

Wernicke’s area is one of two areas of the cerebral cortex associated with speech, the other being Broca’s area. In contrast to Broca’s area, which is primarily concerned with language production, Wernicke’s area is involved in the comprehension of written and spoken language. It is a hotdog-shaped section in the left hemisphere’s temporal lobe.

Wernicke’s aphasia is caused by damage to the Wernicke’s area. This means that the person with aphasia will be able to connect words fluently, but the phrases will be meaningless.

Wernicke’s area is named after Carl Wernicke, a German neurologist and psychiatrist who proposed in 1874 a link between the left posterior section of the superior temporal gyrus and the reflexive mimicking of words and syllables that linked the sensory and motor images of spoken words. He did so based on the location of brain injuries that caused aphasia.

Function of Wernicke’s Area

Transcranial magnetic stimulation research suggests that the Wernicke’s area in the non-dominant cerebral hemisphere plays a role in the processing and resolution of subordinate meanings of ambiguous words, such as “river” when given the ambiguous word “bank.” The Wernicke’s area in the dominant hemisphere, on the other hand, processes dominant word meanings (“teller” given “bank”).

A recent study conducted at the University of Rochester found support for a wide range of speech processing areas by subjecting American Sign Language native speakers to MRI while interpreting sentences that identified a relationship using either syntax (relationship is determined by word order) or inflection (relationship is determined by the physical motion of “moving hands through space or signing on one side of the body”).

Different brain areas were activated, with the frontal cortex (associated with the ability to sequence information) being more active in the syntax condition and the temporal lobes (associated with dividing information into its constituent parts) being more active in the inflection condition. However, these areas are not mutually exclusive and have significant overlap.

These findings imply that, while speech processing is a very complex process, the brain may be using fairly simple, pre-existing computational methods.

Wernicke’s Aphasia

Wernicke’s aphasia, also known as receptive aphasia, is characterized by a significant impairment in language comprehension, despite the fact that speech retains a natural-sounding rhythm and a relatively normal syntax. As a result, language is largely meaningless.

Wernicke’s area is thought to receive information from the auditory cortex and to assign word meanings. Damage to this area causes meaningless speech, often with paraphasic errors and newly created words or expressions.

Paraphasia can be defined as either substituting one word for another (semantic paraphasia) or substituting one sound or syllable for another (phonemic paraphasia).

Speech in paraphasia is often referred to as “word salad,” because it sounds fluent but lacks meaning. Normal sentence structure and prosody are preserved, as are normal intonation, inflection, rate, and rhythm.

Patients are usually unaware that their speech is impaired in this way because they have altered comprehension of their speech. Written language, reading, and repetition are all similarly affected.

Wernicke’s aphasia is caused by damage to the posterior temporal lobe of the dominant hemisphere. The most common cause is a cerebrovascular event, such as an ischemic stroke.

Other causes of focal damage that could lead to Wernicke’s aphasia include head trauma, central nervous system infections, neurodegenerative disease, and neoplasms.

The first step in treating Wernicke’s aphasia is to address the underlying cause. Speech and language therapy is the first-line treatment for aphasia and aims to improve language deficits while also preserving the patient’s remaining language skills.

A secondary goal of therapy after that is to teach the patient how to communicate in different ways so that they can communicate successfully in everyday life. This could include gestures, pictures, or the use of electronic devices.

Location

Wernicke’s area has traditionally been thought to be in the posterior section of the superior temporal gyrus (STG), usually in the left cerebral hemisphere. This area encircles the auditory cortex on the lateral sulcus, the part of the brain where the temporal and parietal lobes meet.

However, there is a lack of consensus on definitions of the location.

Some associate it with the unimodal auditory association in the superior temporal gyrus anterior to the primary auditory cortex. According to functional brain imaging experiments, this is the site most consistently implicated in auditory word recognition.

Others include adjacent parts of the heteromodal cortex in the parietal lobe‘s BA 39 and BA40. Despite the widespread belief in a well-defined “Wernicke’s Area,” the most recent research indicates that it is not a unified concept.

Primary Progressive Aphasia

2015 research from Northwestern Medicine scientists argues for a redrawn brain map of language comprehension based on work with individuals who have a rare form of dementia that affects language, Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA).

Their research shows that word comprehension is actually located in a different brain region: the left anterior temporal lobe, which is more forward than Wernicke’s. And contrary to popular belief, sentence comprehension may be distributed widely across the language network rather than in a single area.

PPA patients with Wernicke’s area damage did not have the same level of word comprehension impairment as stroke patients. Individual words were still understood. And their sentence comprehension was inconsistent; some sentences were understood while others were not.

Emily Rogalski, a Northwestern scientist, performed the imaging on 72 PPA patients with damage inside and outside of Wernicke’s area. She measured the thickness of the cortex in each of these areas.

The thickness of the cortex is an indirect measure of the number of neurons and brain health. The thinning of the cortex in PPA indicates that the disease is destroying neurons.

Rogalski discovered that PPA patients who lost cortical thickness in Wernicke’s area could still understand individual words but had varying degrees of impairment in sentence comprehension. None of these patients had the global type of comprehension impairment described in Wernicke’s aphasia stroke patients.

Only PPA patients with decreased cortical thickness in a region of the brain completely outside of Wernicke’s area, in the front part of the temporal lobe, showed severe word comprehension loss. Because this part of the brain is unaffected by stroke, its role in comprehension was overlooked in previous language maps.

The neurodegenerative disease in PPA does not destroy the underlying fiber pathways that allow language areas to communicate with one another. However, those critical highways passing through Wernicke’s were destroyed in stroke patients.

References:

- Binder JR. Current Controversies on Wernicke’s Area and its Role in Language. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017 Aug;17(8):58.

- Bogen JE, Bogen GM (1976). Wernicke’s region—Where is it?. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 280 (1): 834–43

- DeWitt I, Rauschecker JP (2013). Wernicke’s area revisited: parallel streams and word processing. Brain Lang. 127 (2): 181–91. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2013.09.014

- M-Marsel Mesulam , Cynthia K. Thompson , Sandra Weintraub , Emily J. Rogalski. The Wernicke conundrum and the anatomy of language comprehension in primary progressive aphasia. Brain, June 2015 DOI: 10.1093/brain/awv154

- Newman AJ, Supalla T, Hauser P, Newport EL, Bavelier D (2010). Dissociating neural subsystems for grammar by contrasting word order and inflection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (16): 7539–44

- Wernicke K. (1995). The aphasia symptom-complex: A psychological study on an anatomical basis (1875). In Paul Eling (ed.). Reader in the History of Aphasia: From Franz Gall to Norman Geschwind. Vol. 4. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub Co. ISBN 978-90-272-1893-3