Our five senses constantly flood us with environmental information. One way our brain makes sense of this storm of information is by combining information from two or more senses, such as odors and the smoothness of textures, pitch, color, and musical dimensions.

This crossmodal sensory integration also leads us to associate higher temperatures with warmer colors, lower sound pitches with lower elevations, and colors with specific food flavors — for example, the flavor of oranges with the color of the same name.

A study has now demonstrated experimentally that such unconscious ‘crossmodal’ associations with our sense of smell can influence our perception of colors.

“Here we show that the presence of different odors influences how humans perceive color,”

said lead author Dr. Ryan Ward, of Liverpool John Moores University.

Sensory Deprivation Environment

Ward and colleagues tested for the existence and strength of odor-color associations in 24 adult women and men between 20 and 57 years of age.

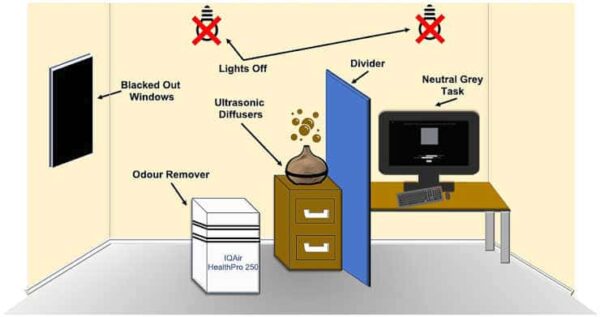

For the duration of the trials, the participants sat in front of a screen in a room devoid of unwanted sensory stimulation. They didn’t wear deodorants or fragrances, and none of them claimed to be colorblind or have a bad sense of smell.

An air purifier was used for four minutes to remove all odors from the isolation room. Then, for five minutes, an ultrasonic diffuser was used to broadcast one of six fragrances (selected at random from caramel, cherry, coffee, lemon, and peppermint, plus unscented water as a control) into the room.

“In a previous study, we had shown that the odor of caramel commonly constitutes a crossmodal association with dark brown and yellow, just like coffee with dark brown and red, cherry with pink, red, and purple, peppermint with green and blue, and lemon with yellow, green, and pink,”

explained Ward.

Participants were shown a screen with a square filled with a random hue (from an unlimited range) and asked to manually adjust two sliders — one for yellow to blue and another for green to red — to change the color to neutral gray. After recording the final choice, the procedure was repeated until all scents had been offered five times.

Non-neutral Overcompensation

Credit: Front. Psychol. 14:1175703. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1175703 CC-BY

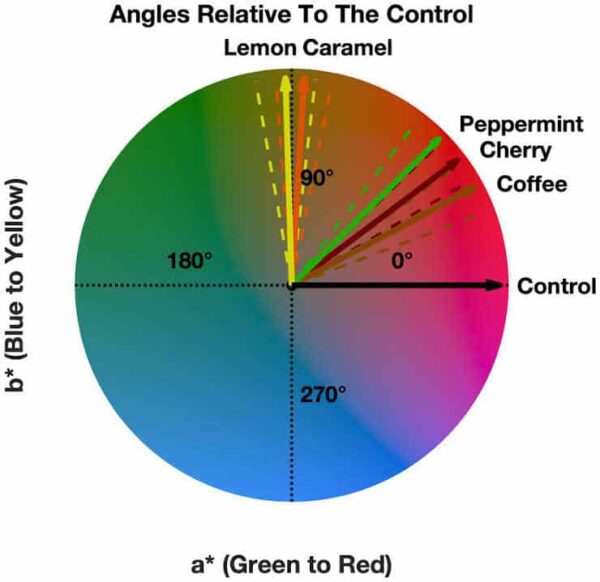

The results showed that participants had a weak but significant tendency to adjust one or both of the sliders too far away from neutral gray. For example, when presented with the odor of coffee, they wrongly perceived ‘gray’ to be more of a red-brown color than true neutral gray.

Similarly, when confronted with the odor of caramel, they mistook a color enhanced in blue for gray. The fragrance thus affected the participants’ color perception in a predictable way.

An exception was when the odor of peppermint was presented: here, the participants’ choice of hue was different from the typical crossmodal association demonstrated for the other odors. As expected, the participants’ selection likewise corresponded to true gray when presented with the neutral scent of water.

“These results show that the perception of gray tended towards their anticipated crossmodal correspondences for four out of five scents, namely lemon, caramel, cherry, and coffee. This ‘overcompensation’ suggests that the role of crossmodal associations in processing sensory input is strong enough to influence how we perceive information from different senses, here between odors and colors.”

said Ward.

Further Study Needed

The researchers stress the need to investigate the extent of these crossmodal associations between odors and colors.

“We need to know the degree to which odors influence color perception. For example, is the effect shown here still present for less commonly encountered odors, or even for odors encountered for the first time?”

said Ward.

One limitation of the study is the number of tested odors. The researchers only tested five odors, and although they found that four out of five of the odors had a mean direction significantly different from the control, it would be beneficial to uncover the extent in which this bias is present and to uncover if the trend toward the expected crossmodal correspondences for a given odor is only true if it also happens to be associated with a warm color.

Abstract

Our brain constantly combines multisensory information from our surrounding environment. Odors for instance are often perceived with visual cues; these sensations interact to form our own subjective experience. This integration process can have a profound impact on the resulting experience and can alter our subjective reality. Crossmodal correspondences are the consistent associations between stimulus features in different sensory modalities. These correspondences are presumed to be bidirectional in nature and have been shown to influence our perception in a variety of different sensory modalities. Vision is dominant in our multisensory perception and can influence how we perceive information in our other senses, including olfaction. We explored the effect that different odors have on human color perception by presenting olfactory stimuli while asking observers to adjust a color patch to be devoid of hue (neutral gray task). We found a shift in the perceived neutral gray point to be biased toward warmer colors. Four out of five of our odors also trend toward their expected crossmodal correspondences. For instance, when asking observers to perform the neutral gray task while presenting the smell of cherry, the perceptually achromatic stimulus was biased toward a red-brown. Using an achromatic adjustment task, we were able to demonstrate a small but systematic effect of the presence of odors on human color perception.

Reference:

- Ward RJ, Ashraf M, Wuerger S and Marshall A (2023) Odors modulate color appearance. Front. Psychol. 14:1175703. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1175703