We are not entirely isolated from our surroundings while we sleep; in fact, we retain the ability to hear and comprehend words, research from the Sleep Pathology Department at Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital in Paris and the Paris Brain Institute indicates.

The findings challenge the fundamental definition of sleep and the clinical criteria that differentiate its various stages.

Researchers have demonstrated that average sleepers are capable of receiving verbal information conveyed through the human voice and reacting to it through facial muscle contractions. This extraordinary ability manifests itself intermittently throughout nearly all stages of slumber, as if windows of communication with the outside world were momentarily opened.

These new findings imply that it may be possible to create standardized communication protocols with sleeping people in order to better understand how mental activity varies throughout sleep. A novel method for accessing the cognitive processes that underpin both normal and disturbed sleep is on the horizon.

Highly Complex Phenomenon

Even though it may appear routine because we do it every night, sleep is a highly complex phenomenon.

Our research has taught us that wakefulness and sleep are not stable states: on the contrary, we can describe them as a mosaic of conscious and seemingly unconscious moments,

explained Lionel Naccache, a neurologist at Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital and a neuroscientist.

It is essential to decipher the brain mechanisms underlying these intermediate states between wakefulness and sleep.

“When they are dysregulated, they can be associated with disorders such as sleepwalking, sleep paralysis, hallucinations, the feeling of not sleeping all night, or on the contrary of being asleep with your eyes open,”

Isabelle Arnulf, head of the Sleep Pathology Department at Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, said.

Contradicting Physiological Indications

Researchers typically employ physiological indications such as particular brain waves detectable through electroencephalography to distinguish between awake and different stages of sleep.

Unfortunately, these markers do not provide a comprehensive picture of what is going on in the minds of sleepers. In fact, they occasionally contradict their statements.

“We need finer physiological measurements that align with the sleepers’ experience. It would help us define their level of alertness during sleep,”

Delphine Oudiette, a cognitive neuroscience researcher, added.

Lucid Narcolepsy

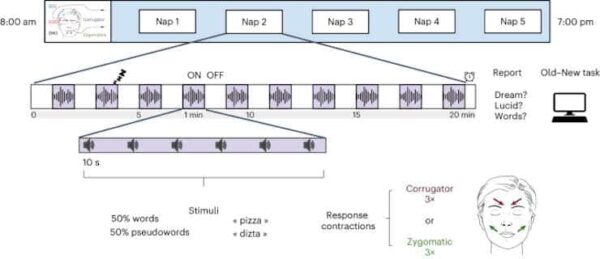

To investigate this possibility, the researchers enlisted the help of 22 people who did not have sleep disorders and 27 patients who had narcolepsy, or uncontrollable episodes of daytime sleepiness. People with narcolepsy have the particularity of having many lucid dreams, in which they are aware of being asleep; some can sometimes even shape their dream scenario as they wish.

Credit: Nat Neurosci (2023). doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01449-7

Furthermore, they easily and quickly enter REM sleep (the stage where lucid dreaming occurs) during the day, making them ideal candidates for studying consciousness during sleep under experimental conditions.

“One of our previous studies showed that two-way communication, from the experimenter to the dreamer and vice versa, is possible during lucid REM sleep,” Delphine Oudiette explained. “Now, we wanted to find out whether these results could be generalized to other stages of sleep and to individuals who do not experience lucid dreams.”

The study’s participants were instructed to take a nap. The researchers administered a “lexical decision” test to them, in which a human voice spoke a succession of actual and made-up phrases.

Participants were required to respond by smiling or frowning in order to be classified into one of these categories. Polysomnography — a complete monitoring of their brain and heart activity, eye movements, and muscle tone — was used to monitor them during the experiment.

Upon waking up, participants had to report whether they had or had not had a lucid dream during their nap and whether they remembered interacting with someone.

“Most of the participants, whether narcoleptic or not, responded correctly to verbal stimuli while remaining asleep. These events were certainly more frequent during lucid dreaming episodes, characterized by a high level of awareness. Still, we observed them occasionally in both groups during all phases of sleep,”

Isabelle Arnulf says.

Privileged Access

The researchers demonstrated that it is possible to forecast the opening of these windows of connection with the environment, i.e., the moments when sleepers were able to respond to stimuli, by cross-referencing these physiological and behavioural data with the subjects’ subjective reports. They were signalled by an increase in brain activity as well as physiological signs typically linked with high cognitive engagement.

“In people who had a lucid dream during their nap, the ability to respond to words and to report this experience upon waking up was also characterized by a specific electrophysiological signature. Our data suggests that lucid dreamers have privileged access to their inner world and that this heightened awareness extends to the outside world,”

Lionel Naccache said.

More research is needed to determine whether the frequency of these windows correlates with sleep quality and whether they can be used to improve certain sleep disorders or facilitate learning.

“Advanced neuroimaging techniques, such as magnetoencephalography and intracranial recording of brain activity, will help us better understand the brain mechanisms that orchestrate sleepers’ behavior,”

Delphine Oudiette concluded.

Finally, these new findings may aid in revising the definition of sleep, which is ultimately very active, perhaps more conscious than we previously imagined, and open to the world and others.

Abstract

Sleep has long been considered as a state of behavioral disconnection from the environment, without reactivity to external stimuli. Here we questioned this ‘sleep disconnection’ dogma by directly investigating behavioral responsiveness in 49 napping participants (27 with narcolepsy and 22 healthy volunteers) engaged in a lexical decision task. Participants were instructed to frown or smile depending on the stimulus type. We found accurate behavioral responses, visible via contractions of the corrugator or zygomatic muscles, in most sleep stages in both groups (except slow-wave sleep in healthy volunteers). Across sleep stages, responses occurred more frequently when stimuli were presented during high cognitive states than during low cognitive states, as indexed by prestimulus electroencephalography. Our findings suggest that transient windows of reactivity to external stimuli exist during bona fide sleep, even in healthy individuals. Such windows of reactivity could pave the way for real-time communication with sleepers to probe sleep-related mental and cognitive processes.

Reference:

- Türker, B., Musat, E.M., Chabani, E. et al. Behavioral and brain responses to verbal stimuli reveal transient periods of cognitive integration of the external world during sleep. Nat Neurosci (2023). doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01449-7