Time is a continuous stream, yet our memories are split into discrete episodes, each of which becomes a part of our own narrative. The role of emotions in memory formation is a puzzle that science has only lately begun to explore.

UCLA scientists have now shown that the shifting emotions evoked by music aid in the formation of distinct and long-lasting memories.

Music was employed in the study to affect the emotions of volunteers executing simple computer tasks. The researchers discovered that the dynamics of people’s emotions transformed normally innocuous experiences into memorable ones.

“Changes in emotion evoked by music created boundaries between episodes that made it easier for people to remember what they had seen and when they had seen it. We think this finding has great therapeutic promise for helping people with PTSD and depression,”

lead author Mason McClay, a doctoral student in psychology at UCLA, said.

Memory Integration vs Separation

People must organize knowledge as time passes because there is too much to remember (and not all of it is useful). Two processes appear to be involved in the transformation of experiences into memories over time: the first integrates our recollections by compressing and combining them into personalized episodes, while the second widens and separates each memory as the experience recedes into the past.

There is a perpetual tug of war between integrating and separating memories, and it is this push and pull that aids in the formation of separate memories. This adaptable process aids in the understanding and meaning-making of one’s experiences, as well as the retention of knowledge.

“It’s like putting items into boxes for long-term storage. When we need to retrieve a piece of information, we open the box that holds it. What this research shows is that emotions seem to be an effective box for doing this sort of organization and for making memories more accessible,”

said corresponding author David Clewett, an assistant professor of psychology at UCLA.

A similar effect could explain why Taylor Swift’s “Eras Tour” has been so effective at eliciting vivid and long-lasting memories: her concert contains meaningful chapters that can be opened and closed to relive intensely emotional experiences.

Tracking Emotional Reactions

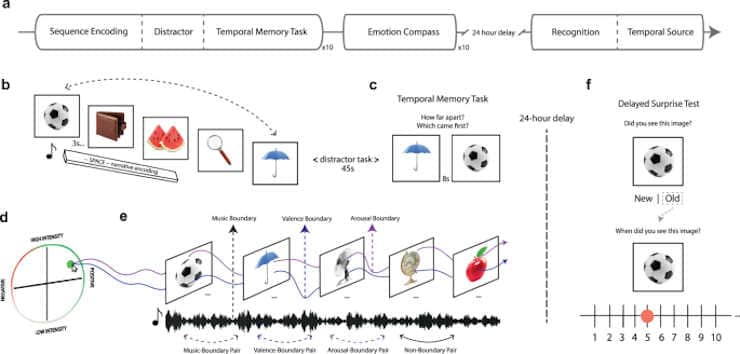

McClay and Clewett, working with Matthew Sachs of Columbia University, commissioned composers to write music that would elicit joyous, anxious, sorrowful, or tranquil emotions of varying intensity. Participants in the study listened to music while visualizing a story to go with a succession of neutral images on a computer screen, such as a watermelon slice, a wallet, or a soccer ball.

They also used the computer mouse to track moment-to-moment changes in their feelings on a novel tool developed for tracking emotional reactions to music.

After completing a task designed to distract them, participants were given pairs of photographs in a random order again. For each pair, they were asked which image they had seen first, and then how far apart in time they thought the two things had been seen.

Weaving Richer Temporal Structures

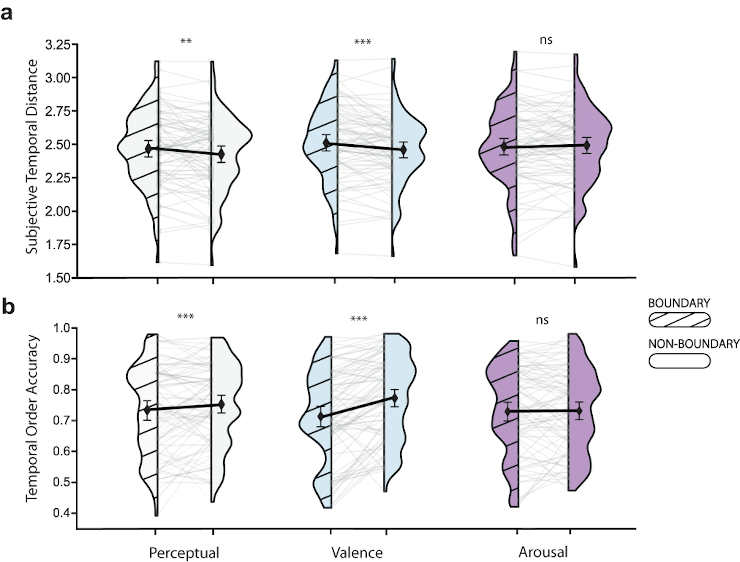

Pairs of objects that participants had seen immediately before and after a change of emotional state — whether of high, low, or medium intensity — were remembered as having occurred farther apart in time compared to images that did not span an emotional change.

Credit: Nat Commun 14, 6533 (2023). doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42241-2

Participants also demonstrated poorer memory for the order of objects spanning emotional fluctuations when compared to items viewed when they were in a more stable emotional state. These findings show that listening to music caused a change in emotion, which pushed fresh memories apart.

“This tells us that intense moments of emotional change and suspense, like the musical phrases in Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody,” could be remembered as having lasted longer than less emotive experiences of similar length. Musicians and composers who weave emotional events together to tell a story may be imbuing our memories with a rich temporal structure and longer sense of time,”

McClay said.

Positive Emotional Valence

The direction of the change in feeling was also important. When the change was toward more pleasant emotions, memory integration was best — that is, memories of consecutive objects seemed closer together in time, and individuals were better at recalling their sequence.

A movement toward more negative emotions, on the other hand (from calmer to sadder, for example), tended to isolate and widen the mental space between fresh memories.

Participants were again polled the next day to test their longer-term memory, and they demonstrated superior recollection for items and moments when their emotions altered, particularly when experiencing extreme positive emotions. This shows that feeling more happy and enthusiastic can help to connect diverse aspects of an experience in memory.

“Most music-based therapies for disorders rely on the fact that listening to music can help patients relax or feel enjoyment, which reduces negative emotional symptoms,”

Sachs said, emphasizing the utility of music as an intervention technique.

“The benefits of music-listening in these cases are therefore secondary and indirect. Here, we are suggesting a possible mechanism by which emotionally dynamic music might be able to directly treat the memory issues that characterize such disorders.”

According to Clewett, these findings may aid in the reintegration of memories that have caused post-traumatic stress disorder.

“If traumatic memories are not stored away properly, their contents will come spilling out when the closet door opens, often without warning. This is why ordinary events, such as fireworks, can trigger flashbacks of traumatic experiences, such as surviving a bombing or gunfire,”

he said.

The team believes they can use positive emotions, possibly through music, to help people with PTSD put that original memory in a box and reintegrate it so that negative emotions don’t spill over into everyday life.

Abstract

Human emotions fluctuate over time. However, it is unclear how these shifting emotional states influence the organization of episodic memory. Here, we examine how emotion dynamics transform experiences into memorable events. Using custom musical pieces and a dynamic emotion-tracking tool to elicit and measure temporal fluctuations in felt valence and arousal, our results demonstrate that memory is organized around emotional states. While listening to music, fluctuations between different emotional valences bias temporal encoding process toward memory integration or separation. Whereas a large absolute or negative shift in valence helps segment memories into episodes, a positive emotional shift binds sequential representations together. Both discrete and dynamic shifts in music-evoked valence and arousal also enhance delayed item and temporal source memory for concurrent neutral items, signaling the beginning of new emotional events. These findings are in line with the idea that the rise and fall of emotions can sculpt unfolding experiences into memories of meaningful events.

Reference:

- McClay, M., Sachs, M.E. & Clewett, D. Dynamic emotional states shape the episodic structure of memory. Nat Commun 14, 6533 (2023). doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42241-2

Last Updated on January 2, 2024