The Elaboration Likelihood Model was proposed by social psychologists Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo in the early 1980s. They introduced this dual process theory to elucidate the processes that underpin how an individual is persuaded. The model emerged from their investigation into the varying effects of persuasive communications and the consistency of attitude changes.

The elaboration likelihood model (ELM) is based on four central ideas.

- When a person encounters some type of communication, they may process it with varied degrees of thought (elaboration), ranging from low to high. Different goals, abilities, opportunities, and so on are all contributing factors to elaboration.

- There are several psychological processes of transformation that act to varied degrees depending on a person’s level of elaboration. On the lower end of the spectrum are processes that involve minimal cognition, such as classical conditioning and mere exposure. Expectancy-value and cognitive response processes are at the higher end of the continuum, requiring comparatively more thought. When lower elaboration processes predominate, a person is said to be using the peripheral route, as opposed to the central route, which involves mostly high elaboration processes.

- The level of thought used in a persuading situation shapes how important the resulting attitude is. Attitudes established by high-thought, central-route processes are more likely to remain over time, resist persuasion, and influence the direction of other judgments and behaviors than attitudes generated through low-thought, peripheral-route processes.

- Any one variable can play numerous functions in persuasion, such as providing a cue to judgment or influencing the direction of thought about a message. According to the ELM, the extent of elaboration determines a variable’s specialized role.

Dual Processes in Persuasion

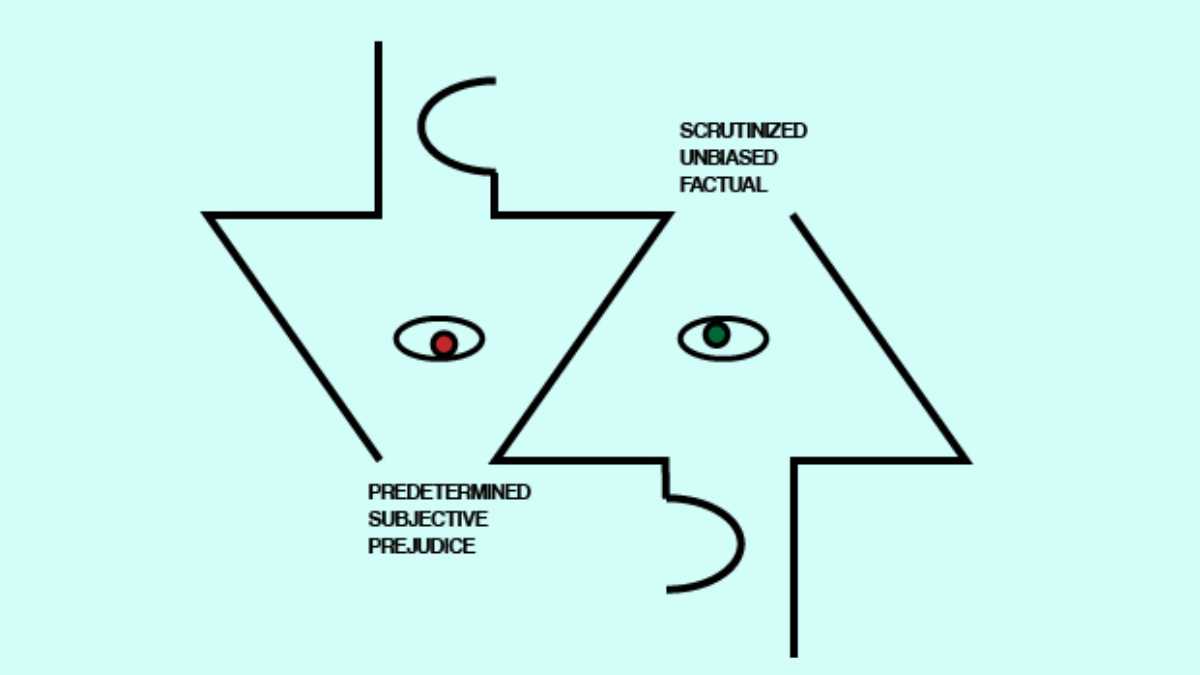

The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion posits two distinct pathways through which information can influence attitude change: the central route and the peripheral route. According to the model, there are various unique processes of change along the “elaboration continuum” that range from low to high.

When low-level operation processes determine attitudes, persuasion takes the periphery route. When attitudes are determined by high-end operating processes, persuasion takes the central channel.

Central Route

The central route is employed when the message recipient is both motivated and able to think about the message and its topic. When people process information centrally, their cognitive reactions, or elaborations, are far more relevant to the material, whereas when they process peripherally, they may rely on heuristics and other rules of thumb to elaborate on a message.

People at the high end of the elaboration continuum assess object-relevant information in connection to schemas that they already have, resulting in a reasoned attitude backed by knowledge. It is critical to evaluate two types of criteria that determine how much one elaborates on a compelling message.

The first set of criteria influences our motivation to elaborate, whereas the second set influences our ability to elaborate. Individual variables such as the requirement for cognition or a personal interest in the message’s content may drive motivation to process the information.

The central route has two advantages over the peripheral route: attitude changes stay longer and are more predictive of behavior. Overall, when people’s motivation and capacity to analyze messages and construct elaborations declines, peripheral cues in the circumstance become more significant in their message processing.

Peripheral Route

The peripheral route to persuasion is employed when the message recipient has little or no interest in the subject and/or a limited ability to process it. Receivers at the low end of the elaboration continuum do not study the information as extensively.

When using the peripheral method, they are more likely to rely on overall perceptions (e.g., “this feels right/good”), early sections of the message, their own mood, positive and negative cues from the persuasion context, and so on. Because people are “cognitive misers” who want to save mental effort, they frequently take the peripheral route and thus rely on heuristics (mental shortcuts) when processing information.

When an individual is not motivated to centrally process an issue due to a lack of interest in it, or when the individual lacks the cognitive ability to do so, these heuristics can be very compelling. Some widely employed heuristics include commitment, social evidence, scarcity, reciprocation, authority, and liking the person convincing you, as outlined in Robert Cialdini’s Principles of Social Influence.

Furthermore, credibility can be employed as a heuristic in peripheral thinking because if a speaker is perceived to have more credibility, the listener is more likely to believe the message. Credibility is a low-effort and fairly reliable method of providing us with an answer as to what to do and/or believe without requiring us to put in a lot of thought.

If these peripheral influences go unnoticed, the message recipient will most likely keep their previous attitude toward the message. Otherwise, the individual will have a temporary shift in his attitude about it. This attitude shift can be long-lasting, however it is less likely to occur than with the central route.

Influences on Route

Motivation (the desire to process the message) and ability (the ability to critically evaluate) are the two most influential criteria in determining which processing route an individual uses. Attitude and personal significance have an impact on motivational levels. Distractions, cognitive activity (the extent to which many tasks engage cognitive processes), and overall knowledge all have an impact on an individual’s ability to elaborate.

Attitudes about a message can influence motivation. According to cognitive dissonance theory, when people are confronted with new information (a message) that contradicts their existing beliefs, ideas, or values, they are motivated to minimize the dissonance in order to feel at ease with their own views. Personal relevance can also affect an individual’s degree of motivation.

The need for cognition is another aspect that influences an individual’s level of motivation. Individuals who love thinking more than others tend to engage in more effortful thinking because it provides them with intrinsic pleasure, regardless of the relevance of the problem or the necessity to be correct.

Ability involves the availability of cognitive resources (for example, the absence of time constraints or distractions) as well as the necessary knowledge to assess arguments. Distractions (for example, noise in a library where someone is attempting to read a journal article) can impair a person’s capacity to digest information.

Cognitive busyness, which can also function as a distraction, reduces the cognitive resources available for the task at hand (evaluating a message). Another indicator of skill is acquaintance with the relevant subject. Though they are neither distracted or cognitively busy, a lack of knowledge can prevent people from engaging in deep thinking.

Persuasion Outcome Variables

A variable is defined as something that can raise or diminish a message’s persuasiveness. Attractiveness, attitude, and skill are just a few elements that might affect persuasiveness. Variables can be used as arguments or peripheral cues to influence the persuasiveness of a message. According to the ELM, changing the quality of an argument or providing a cue in a persuasive environment can influence the persuasiveness of a communication and the attitudes of recipients.

Under high elaboration, a given variable (e.g., expertise) can serve as an argument (e.g., “If Einstein agrees with the theory of relativity, then this is a strong reason for me to as well”) or a biasing factor (e.g., “If an expert agrees with this position, it is probably good, so let me see who else agrees with this conclusion”) at the expense of contradicting information.

A variable may serve as a peripheral cue under low-elaboration conditions (for example, the notion that “experts are always right”). While this is comparable to the Einstein example above, it is a shortcut that, unlike the Einstein example, requires no thought.

Under moderate elaboration, a variable can direct the extent of information processing (for example, “If an expert agrees with this position, I should really listen to what they have to say”). If participants are under moderate elaboration settings, variables may objectively boost or lessen persuasiveness, or they may bially motivate or prevent them from generating a certain concept.

Applications and Implications

The application of ELM in social and health campaigns speaks to its capacity to drive sustained behavioral change. This is particularly critical in responses to events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where understanding the mechanics behind persuasion is pivotal.

Mark W. Susmann et al. published a study in the European Review of Social Psychology that outlined the use of the elaboration likelihood model to arrange persuasion strategies and determine which ones resulted in behavior modification depending on interest and incentive to respond.

The study classified the theory as “useful” when used to assess persuasion during the pandemic “as it allows health communicators to identify variables that are likely to lead to the greatest amount of persuasion depending on whether recipients are likely to process the message deeply.”

Another study in the Journal of Health Communications from Denise Scannell et al. examined the conversation surrounding vaccinations on Twitter, using the elaboration likelihood model to compare pro- and anti-vaccine statements. The study discovered that pro-vaccine communications depended primarily on the central processing route, whereas anti-vaccine messages used the peripheral processing route more, but the difference was not as significant.

Mental Health Profession

The more credible a mental health counselor is regarded as, the more likely counseling clients are to believe the counselor’s guidance is effective. However, the extent to which the client understands the information communicated by the counselor has a significant impact on counselor credibility.

As a result, it is critical that counseling clients have no trouble understanding their counselor. Metaphors can be useful in this situation. Metaphors necessitate a greater level of elaboration, which engages the central rounte of processing.

Walter Kendall proposed employing metaphor in counseling as a valid strategy for helping clients understand the message/psychological knowledge communicated by the client. When a client hears a metaphor that speaks to them, they are significantly more likely to trust and develop a favorable connection with the counselor.

Media and Advertising

In media and advertising, the ELM underscores the importance of crafting messages that target varying levels of audience involvement. High-involvement individuals are more likely to be persuaded through the central route, where deep processing of message content occurs.

For example, an in-depth and factual article on a product’s benefits may influence a consumer’s lasting attitude. Conversely, when involvement is low, the peripheral route becomes prominent, and aspects like the attractiveness of the spokesperson or the number of endorsements could sway audiences more effectively.

- Central Route: Focus on quality and depth of message content.

- Peripheral Route: Utilize cues like celebrity endorsements or repetition.

Challenges and Criticisms of Elaboration Likelihood Model

Critics of the Elaboration Likelihood Model target its psychological foundation, particularly how people process information and change their attitudes. One criticism points to the dual-process nature of the model, arguing that the division between central and peripheral routes may not account for the complexity of human cognition.

The heuristic-systematic model has been offered as a counterpoint, positing that people use heuristics or systematic processing rather than the binary routes proposed by the ELM.

Additionally, the model has been questioned for its underestimation of bias, suggesting that individuals’ pre-existing biases can impact their likelihood of elaboration, thus affecting the model’s predictive power. This brings to light a need for further exploration into how deeply ingrained attitudes might lead to a resistance to persuasion, which the ELM does not fully address.

The elaboration likelihood continuum should demonstrate that a human can naturally evolve from high involvement to reduced involvement, with the appropriate consequences. This continuum can explain for the rapid transition between the central and peripheral channels, but there has been a lack of extensive and empirical testing since the beginning. However, research has been conducted under three unique conditions: high, low, and moderate.

Morris, Woo, and Singh asked in 2005 why emotion was not included in ELM’s description of cognitive processes. According to the authors, the theory suggests that attitude change is primarily influenced by cognitive (central) signals rather than emotive (peripheral) ones. Morris, Wood, and Singh argue that every message contains an emotional component as well. They claim that emotions have a larger influence in attitude development than the method utilized to process information.

Methodological Concerns

Methodological concerns have been raised regarding how researchers have operationalized and tested the Elaboration Likelihood Model. These concerns primarily relate to the variables used in experimental settings to measure persuasion and attitude change. Critics suggest that the variables often fail to encompass the full range of human experiences and can lead to inadequacies in replicating real-world scenarios.

Furthermore, there may be an over-reliance on laboratory experiments, which might not accurately simulate the complexity of naturalistic persuasion contexts. This lab-based bias potentially limits the model’s applicability to more dynamic communication situations encountered outside experimental controls.

Choi and Salmon, for example, questioned Petty and Cacioppo’s notion that correct product recall resulted in high involvement. They claimed that high engagement is more likely to be caused by other factors, such as the sample population, and that weak/strong arguments in one study will result in different involvement characteristics in another.

References:

- Cialdini, Robert (2001). Influence : science and practice (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0321011473

- Choi, S. M.; Salmon, C. T. (2003). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion after two decades: A review of criticisms and contributions. The Kentucky Journal of Communication. 22 (1): 47–77

- Eagly A. and Chaiken S. (2003) The Psychology of Attitudes. Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich, Fort Worth, Texas

- Fonagy, Peter; Allison, Elizabeth (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy. 51 (3): 372–380. doi: 10.1037/a0036505

- Hu, B. (2013). Examining elaboration likelihood model in counseling context. Asian Journal of Counselling. 20 (1–2): 33–58

- J. Kitchen, P., Kerr, G., E. Schultz, D., McColl, R., & Pals, H. (2014). The elaboration likelihood model: review, critique and research agenda. European Journal of Marketing, 48(11/12), 2033-2050.

- Lien, Nai-Hwa (2001). Elaboration Likelihood Model in Consumer Research: A Review. Proceedings of the National Science Council Part C: Humanities and Social Sciences. 11 (4): 301–310

- Morris, J. D.; Singh, A. J.; Woo, C. (2005). Elaboration likelihood model: A missing intrinsic emotional implication. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing. 14: 79–98. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740171

- Petty, Richard E.; Cacioppo, John T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387963440

- Petty, Richard E.; Cacioppo, John T. (1986). The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Communication and Persuasion. pp. 1–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4964-1_1

- Petty, R.; et al. (2002). Thought confidence as a determinant of persuasion: the self validation hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 82 (5): 722–741. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.722

- Scannell, Denise; Desens, Linda; Guadagno, Marie; Tra, Yolande; Acker, Emily; Sheridan, Kate; Rosner, Margo; Mathieu, Jennifer; Fulk, Mike (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine Discourse on Twitter: A Content Analysis of Persuasion Techniques, Sentiment and Mis/Disinformation. Journal of Health Communication. 26 (7): 443–459. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2021.1955050

- Susmann, Mark W.; Xu, Mengran; Clark, Jason K.; Wallace, Laura E.; Blankenship, Kevin L.; Philipp-Muller, Aviva Z.; Luttrell, Andrew; Wegener, Duane T.; Petty, Richard E. (2022-07-03). Persuasion amidst a pandemic: Insights from the Elaboration Likelihood Model. European Review of Social Psychology. 33 (2): 323–359. doi:10.1080/10463283.2021.1964744