Are those with higher incomes happier in their daily lives? Although it seems like a simple question, previous research has produced conflicting results, leaving uncertainty about the answer.

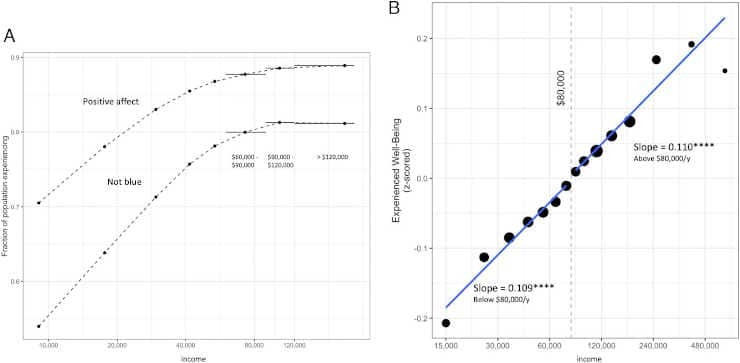

Foundational research from Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton of Princeton University, published in 2010, found that daily happiness increased as annual income increased, but above $75,000, it levelled off, and happiness peaked. In contrast, research by the University of Pennsylvania’s Matthew Killingsworth that was published in 2021 discovered that happiness increased steadily with income well beyond $75,000, without any signs of a plateau.

The two formed an adversarial collaboration to resolve their differences, with Penn University Professor Barbara Mellers serving as arbiter. The trio shows in a new paper that higher incomes are associated with higher happiness levels on average.

Wealthy but Unhappy

Zoom in, however, and the relationship becomes more complicated, revealing that within that overall trend, an unhappy cohort within each income group shows a sharp increase in happiness up to $100,000 annually, then plateaus.

“In the simplest terms, this suggests that for most people, larger incomes are associated with greater happiness,”

said lead paper author Killingsworth.

People who are financially well-off but unhappy are an exception. For example, if you’re wealthy but unhappy, more money won’t help. More money was associated with higher happiness to varying degrees for everyone else.

Mellers observed that no single relationship connects emotional well-being and income.

“The function differs for people with different levels of emotional well-being,”

she said. Specifically, for the least happy group, happiness increases with income until $100,000, then declines as income increases. Happiness increases linearly with income for those in the middle range of emotional well-being, and the association accelerates above $100,000 for the happiest group.

Adversarial Collaboration

The researchers began this collaborative effort with the realization that their previous work had resulted in different conclusions. Killingsworth’s 2021 study did not show a flattening pattern, whereas Kahneman’s 2010 study did.

As the name implies, an adversarial collaboration — a concept developed by Kahneman — aims to resolve scientific disputes or disagreements by bringing together opposing parties and a third-party mediator.

Killingsworth, Kahneman, and Mellers focused on a new hypothesis positing the existence of both a happy majority and an unhappy minority. They hypothesized that for the former, happiness increases as income increases; for the latter, happiness improves as income increases but only up to a certain income threshold, after which it stagnates.

To test this new hypothesis, they searched for the flattening pattern in data from Killingworth’s study, which he had collected using his app Track Your Happiness.

The app randomly contacts participants several times per day with a series of questions, including how they feel on a scale from “very good” to “very bad.” Using an average of the individual’s happiness and income, Killingsworth draws conclusions about the relationship between the two variables.

Plateau in Happiness

Early on in the new partnership, the researchers realized that the 2010 data, which revealed the happiness plateau, had, in fact, measured unhappiness rather than happiness.

“It’s easiest to understand with an example,”

Killingsworth said.

Imagine a cognitive test for dementia that healthy individuals pass with relative ease. Although such a test could detect the presence and severity of cognitive dysfunction, it would reveal little about general intelligence, as most healthy individuals would receive a perfect score.

“In the same way, the 2010 data showing a plateau in happiness had mostly perfect scores, so it tells us about the trend in the unhappy end of the happiness distribution, rather than the trend of happiness in general. Once you recognize that, the two seemingly contradictory findings aren’t necessarily incompatible,”

Killingsworth said.

And what they discovered confirmed this possibility in a stunningly clear manner. When the researchers examined the happiness trend for unhappy people in the data from 2021, they discovered the same pattern as in 2010: happiness rises relatively steeply with income and then levels off.

The two seemingly contradictory findings are actually supported by astonishingly consistent data.

Resolving Scientific Conflict

Without the collaboration of the two research teams, reaching these conclusions would have been difficult, according to Mellers, who suggests that there is no better way to resolve scientific conflict than through adversarial collaborations.

“This kind of collaboration requires far greater self-discipline and precision in thought than the standard procedure,” she said. “Collaborating with an adversary, or even a non-adversary, is not easy, but both parties are likelier to recognize the limits of their claims.”

That is exactly what occurred, resulting in a better understanding of the relationship between money and happiness.

If you believe Killingsworth, these results have important practical ramifications. One example is how they might influence discussions about tax policy and employee pay. And naturally, they matter to individuals as they make decisions about their careers or weigh the benefits of a higher income against other considerations, as Killingsworth put it.

He concluded that money isn’t the be-all and end-all of emotional well-being.

“Money is just one of the many determinants of happiness,”

he said, adding that money is not the key to happiness, but it can certainly help some.

Reference:

- Matthew A. Killingsworth, Daniel Kahneman, and Barbara Mellers. Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2208661120

Last Updated on September 20, 2023