A baby crying not only demands our attention, it also changes executive function in the brain, the very neural and cognitive processes we use to make everyday decisions.

A new study looked at the effect infant vocalizations, in this case audio clips of a baby laughing or crying, had on adults completing a cognitive conflict task. Researchers used the Stroop task, in which participants are asked to rapidly identify the color of a printed word while ignoring the meaning of the word itself.

David Haley, associate professor of psychology at the University of Toronto Scarborough, said:

“Parental instinct appears to be hardwired, yet no one talks about how this instinct might include cognition. If we simply had an automatic response every time a baby started crying, how would we think about competing concerns in the environment or how best to respond to a baby’s distress?”

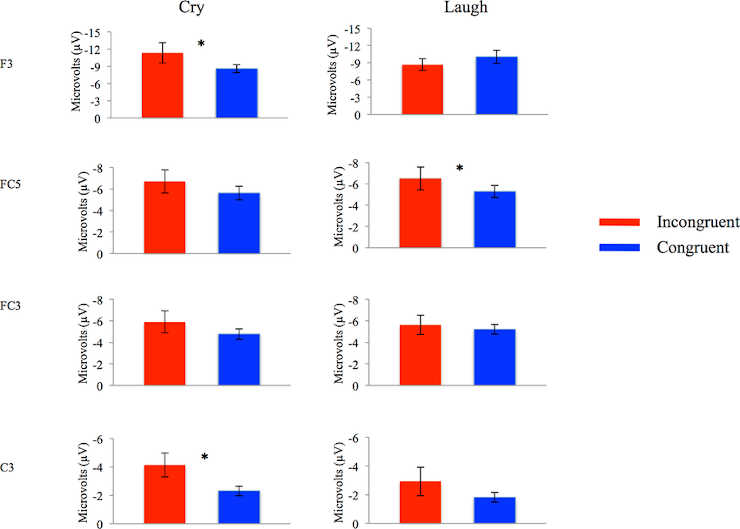

Brain activity was measured using electroencephalography (EEG) during each trial of the cognitive task, which took place immediately after a two-second audio clip of an infant vocalization.

Greater Cognitive Conflict Processing

The findings show that infant cries reduce attention to a task at hand and trigger greater cognitive conflict processing than infant laughs. Cognitive conflict processing is important because it controls attention—one of the most basic executive functions needed to complete a task or make a decision, Haley says.

“Parents are constantly making a variety of everyday decisions and have competing demands on their attention,”

says lead author Joanna Dudek, a graduate student in Haley’s Parent-Infant Research lab.

“They may be in the middle of doing chores when the doorbell rings and their child starts to cry. How do they stay calm, cool, and collected, and how do they know when to drop what they’re doing and pick up the child?”

A baby’s cry has been shown to cause aversion in adults, but it could also be creating an adaptive response by “switching on” the cognitive control parents use in effectively responding to their child’s emotional needs while also addressing other demands in everyday life, Haley says.

“If an infant’s cry activates cognitive conflict in the brain, it could also be teaching parents how to focus their attention more selectively.

It’s this cognitive flexibility that allows parents to rapidly switch between responding to their baby’s distress and other competing demands in their lives—which paradoxically, may mean ignoring the infant momentarily.”

The findings add to a growing body of research suggesting that infants occupy a privileged status in our neurobiological programming, one deeply rooted in our evolutionary past. But, it also reveals an important adaptive cognitive function in the human brain.

The next steps will be to look at whether there are individual differences in the neural activation of attention and conflict processing in new mothers that may help or hinder their capacity to respond sensitively to their own infant’s cry.

Reference:

- Dudek J, Faress A, Bornstein MH, Haley DW (2016). Infant Cries Rattle Adult Cognition. PLoS ONE 11(5): e0154283. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154283

Last Updated on November 23, 2023